ARIA/APOLOGY: An ironic acknowledgment

of the co-existence of art and evil?

|

At first, Seán Curran’s dance looks like a formal exposition of movement, but after a while you begin to imagine webs of social interactions, relationships, and hidden histories. His ability to bring about this human resonance is one of the things that make him an intriguing choreographer. Curran, who started as a Boston Irish stepdancer, brought his 10-year-old company to the Tsai Center last weekend as the first of this season’s Celebrity Series dance offerings.

The Nothing That Is Not There and the Nothing That Is (1998) is set to five recorded piano pieces from Leos Janácek’s On an

Overgrown Path. Although both the dance and the music seem to be latter-day elaborations on folk-dance fundamentals, Curran resists the almost descriptive, post-romantic feel of the score. The four dancers (Nora Brickman, Evan Copeland, Francesca Roma and Kevin Scarpin) clump and tilt around on flexed feet, angling their arms out in parallel, palms-flat gestures.

There’s a certain robotlike rigidity in this movement, but then the mechanical feeling will pull up as the dancers look intently at one another, or bump into a different gear. The two small women streak back and forth in soaring jetés. The men slowly wrestle each other to the ground. Rather than illustrating the score, the dancers seem to absorb its implications of sociability and sentiment.

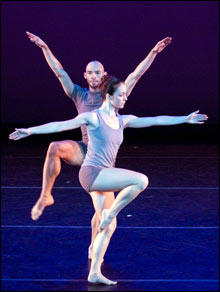

In Aria/Apology, from 2005, we hear recorded confessions from people who’ve committed senseless crimes and gotten away with them — they’re not particularly repentant, they just want to get something off their chests — alternating with sublime Handel arias sung by Renée Fleming. The dancers listen to the casual rapists and murderers, the gorgeous music. Brickman and Copeland do a tender duet with the gracious arms and delicate stepping of a Baroque dance. Falling softly, rolling out of a long, breathless handstand, Scarpin seems to empathize with the victims of a homophobic predator. Two couples duet simultaneously, at one point doing the same movements but with one couple reversing the other’s gender roles. Perhaps the whole dance is an ironic acknowledgment of the co-existence of art and evil.

Curran seems to be incorporating the percussive toughness of his rhythm-dance background into a more fluid movement style, with a more flexible attachment to the music. Social Discourse, which was having its world premiere, uses selections from Radiohead Thom Yorke’s controversial The Eraser. Yorke sings in a high tenor against various complicated rhythm tracks, but the dancers seem to ignore this in the beginning. Or maybe I was just attracted to how much more twisting and spiraling there was in their movement than I’d seen in the previous dances.

As the dance went on, in their duets and solos, they seemed increasingly drawn into the pulse, picking up on the big rhythmic beats of the music, till they worked up to a group consensus that played with the fast, complicated rhythms. The dance was still about the same approach-retreat, push-pull, lift-and-carry interactions we’d seen earlier, but its rapprochement with the music was satisfying in a different, more subtle way.

Seán Curran doesn’t dance much anymore, but he performed the astonishing solo St. Petersburg Waltz (2005), to music from Meredith Monk’s Volcano Songs. Over nine riveting minutes he suggested a whole village full of characters, or a single character’s intense inner life. In a high-collared shirt with the sleeves rolled up, a tie, a black vest with a watch chain in the pocket, a black fedora, pants, and bare feet, he seemed to be an uncle from a few generations ago. A butcher, maybe, or a postal clerk, a man who deals with lots of people but who’s introspective and maybe a little shy.

He dances or hums to himself, looks over his shoulder, holds animated conversations with invisible acquaintances, takes a turn around a dance floor with an invisible woman. Into this stream of busy interactions he flashes insincere salutes, militant struts, even a Nazi “Sieg Heil!” For a minute he appears to have been captured. At the end of the dance he’s bowing from the waist to an invisible superior.

I don’t know whether Curran was creating a portrait of a specific person or conveying the experiences of many persons. Maybe he was remembering the Holocaust; maybe he was reminiscing about a life as a Main Street mediocrity. Whoever he was, I recognized him.