FORCED OUT: While a few parts of Petrella’s case remain unclear, his termination reflects the chief’s

heightened reliance on Internal Affairs. |

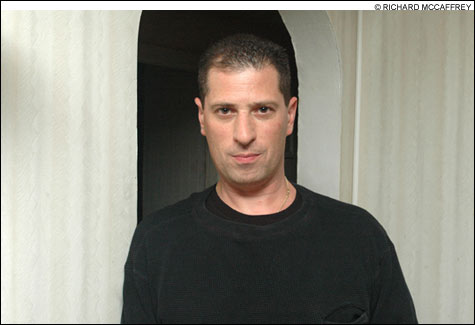

At age 42, former Providence Police sergeant Steven Petrella has the look of a besieged man. Pacing frenetically, gesturing, and periodically stooping to light cigarettes, Petrella cuts a strange, embattled figure against the suburban stillness of the driveway outside his Warwick home.

It is 11 pm on a recent Thursday. For hours, Petrella has been narrating the story of what he sees as his unjust termination in 2005 from the Providence Police — a situation for which he blames his former employer, the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), and especially the department’s high-profile leader, Colonel Dean Esserman.

It is a story that seems to be consuming Petrella. How he, a 12-year veteran of the Providence department, lost the chance to fight for his job because of a missed deadline for an administrative hearing.

While it’s hard to know if there’s more to the case, the underlying details involve a 2003 episode in which Petrella traveled, while on-duty, to Cranston and agreed to return to the station a mini-bike that had been seized by another officer. Though Petrella says he did nothing wrong, the department suspected him of trying to cover for the other officer, who was later convicted of embezzlement and fired.

The fallout is all the more striking because of how some other Providence police officers who have run into trouble, including some of those implicated in a cheating scandal under former chief Urbano Prignano Jr., have fared far more favorably, for various reasons.

And Petrella is only one of many Providence officers who have lost their jobs since Esserman, who was recruited by Mayor David N. Cicilline, arrived in 2003.

Inspector Frank Colon, the director of Internal Affairs, declines to reveal how many officers have lost their jobs — because, he says, it would be bad for morale — but it’s clear that Esserman has raised the focus on internal discipline. Colon says that more officers have been fired, demoted, or disciplined under Esserman than during any comparable period in the past two decades. Previously, there was a lower threshold for becoming part of Internal Affairs’ six-person staff (which the FOP says has doubled under Esserman); now, says Colon, those who police the police must, at minimum, attain the rank of detective.

For years under former Mayor Vincent A. “Buddy” Cianci Jr., Providence’s dysfunctional and politicized police department was marked by scandal, a reputation for using excessive force, and a lack of accountability. In this respect, Esserman — who has been credited with bringing about a far more responsive and more effective police department, as well as significant drops in violent crime (see “Provi¬dence: safer than you think?,” News, May 24) — may be trying to rid the force of what he considers problem officers.

Nevertheless, Petrella says that his case raises questions about the success of internal reforms in the department. “I didn’t lose my job — they took it from me,” he says. “Where’s the integrity in this?”

In September, Petrella’s lawyer, John B. Harwood, the former Speaker of the Rhode Island House of Representatives, filed a Superior Court lawsuit against the Fraternal Order of Police, accusing the union of failing to make a timely filing of the pa¬per¬work needed to guarantee the Officer’s Bill of Rights hearing that might have saved Petrella’s job. It’s the first suit against the 900-member union in recent memory.

Moving forward his case in court remains the sole hope for the former officer, whose sense of betrayal about the Providence Police Department is palpable, punctuating his nearly every sentence. “I put on a bulletproof vest for 12 years for the city,” says Petrella, “and they just kicked me to the curb.”