THE RED BALLOON: Who’s your friend? |

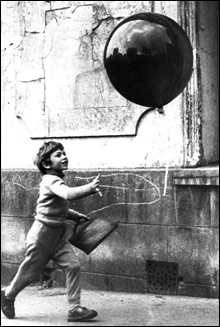

There is no more-enchanting Thanksgiving outing — for children or adults — than the double bill of reissued Albert Lamorisse short films, Crin-blanc|White Mane (1953) and Le ballon rouge|The Red Balloon (1956), that’s getting a run at the Kendall Square starting this Friday. Both focus on unconventional, emblematic childhood friendships. In the first, Folco, a boy from a farming family in Camargue region in the south of France, catches a magnificent white horse, the leader of a pack of wild steeds, and rescues him from hunters who would break and sell him. In the second, a Parisian schoolboy (played by the director’s son, Pascal Lamorisse) climbs up a balcony to release a trapped red balloon, whereupon, self-willed and persistent, it becomes his constant companion.The Red Balloon is whimsical; White Mane (a small masterpiece) touches, in 31 minutes, all the emotions of a classic coming-of-age picture about a child and a legendary animal, like National Velvet, The Yearling, or The Black Stallion. (It’s clear that Carroll Ballard, who made The Black Stallion, owes a debt to Lamorisse.) In both movies, the object of the boy’s affection is an embodiment of the spirit of childhood that can’t be constrained by the traditions of bourgeois society (in Red Balloon) or repressed by the machinations of the self-interested, mercenary adult world (in White Mane). In Red Balloon, Lamorisse deals with these enemies of the youthful drive toward freedom comically and with tremendous charm. When the boy leaves the balloon outside the schoolroom, it slips in unbidden through an open window, and the principal punishes the boy by locking him in an empty room (solitary) for the day; the balloon follows the principal down the street and butts him on the head. When it finds its way into church, this intrusion of the holiday impulse into a sanctified space causes a scandal, and the boy is thrown out. In both scenes, Lamorisse leaves us outside these solemn institutions, so we see the set-up — the mischievous balloon trailing its pal into places where it hasn’t been invited — and the end of the explosion that results. Both are like perfectly calibrated sequences from silent comedies. (Aside from the musical score, there’s almost no dialogue, and most of it is nonsense, like the argument of the jabbering industrialists in Vittorio De Sica’s Miracolo a Milano, from the same era.)

Both the rural setting and the look of Alain Emery, the young actor who plays Folco, place White Mane far from the buttoned-down world the ostentatious red balloon keeps tweaking (which, however, includes an element of savagery: young thugs who attack the balloon with stones). Folco lives near the Rhône, and he’s at home in nature; in one sublime scene we see him feeding an ostrich. When the hunters try to lure the horse out of the marsh by setting fire to it, the country-bred boy knows exactly what to do. In The Red Balloon, the balloon is the intruder, but in White Mane these callous men take that role, and they care so little for the environment that they don’t think twice about destroying it in order to get what they want. The movie’s ending, simultaneously joyous and sad, suggests there’s no future for the idyllic life Folco has known — that the greed and danger represented by the hunters can’t be excised or contained. He rides off with the horse to an unseen island where, the narrator tells us, boys and horses can cavort together happily. It’s a variation on the final, breathtaking scene of The Red Balloon, where all the balloons in Paris float away from their owners and gather to lift the child into the sky. Obviously there’s no place in the modern world for wild horses or wild balloons, so Lamorisse had to invent one.