|

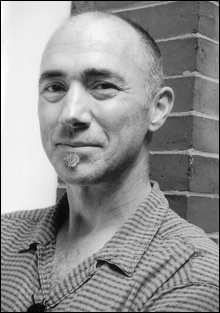

Lake Baikal fills a fracture in the surface of Siberia that’s 25 million years old, 395 miles long, and a mile deep. It’s the world’s largest, deepest, most ancient body of fresh water, and a mythic spot in the minds of many Russians — for its scale, yes, but also for the lake’s mysterious, now endangered, ability to keep itself pristine, thanks to a unique self-cleansing ecosystem. Peter Thomson, founding editor and producer of the Somerville-based NPR environmental news show Living on Earth, journeyed to Lake Baikal from Boston, via trains and boats and cars, after his marriage crumbled. Some people join a gym after a divorce; Thomson, 48 years old, and currently living in Jamaica Plain, embarked on a trip around the world toward this great lake — “God’s own reservoir,” as he terms it. His new book, Sacred Sea: A Journey to Lake Baikal (Oxford University Press, 320 pages, $29.95), documents his trip in a blend of environmental journalism, travel narrative, and memoir. It’s a portrait of a place, its people, and its problems. It’s also an honest look at how far we have to go to get home again.Sitting at Newbury Street’s Trident Café recently, Thomson, who’s got an ageless look about him — a soul patch and a spark behind his eyes masks any world-weariness — talks about the process of writing the book, the trip itself, how our actions reverberate, and how to tell a narrative. “With a big story,” he says, such as something on the scale of Baikal, “what I learned to do is to humanize it, to distill it down to a core essence around which you can build the bigger story.” And so it is in Sacred Sea: straight reporting about mini-shrimp and pollutants and the people who exist on Baikal’s shores alternate with personal details of Thomson’s marriage and family, as well as his reactions to the place (on entering the waters for the first time: “the world is suddenly black and silent, as black and silent as space, and you’re floating weightlessly like in space too . . . except you don’t have a suit on, in fact there’s nothing at all between you and this hostile new environment”).

Regardless of whether the tale is large or small, “there’s nothing in the environmental arena that’s unique to a particular place,” says Thomson. Which means that writing about the faraway wintry exileland of Siberia can resonate here. The mentality exists in Russia that Baikal can take anything that gets thrown at it, that toxic paper factories and a growing local population can’t harm it, that its ability to cleanse itself is bigger and more powerful than any potential human threat. Similarly, in the United States, the perception exists that “there’s always more,” says Thomson. “If paradise gets destroyed, we move and start over. We have this idea as a country of our limitless ability to build and build and build. And Siberia has the same notion of the frontier, of the infinite ability to expand.”

When asked whether he’ll return to Russia, Thomson says he wants to focus his energies “back toward places where I live, where my life is, my homefront.” The US, he explains, has its own problems, ones he wants to bring into greater focus, issues of consumption and appetite, how our actions, even the smallest ones — what we drive, what we eat — have consequences. “We are fundamentally a part of an infinite number of relations,” says Thomson. “Everything we do reverberates.” And he stresses the importance of people’s relationships to place: our lives are defined by the places we live and work and visit, “and, ultimately, whether those places are preserved and protected and treated well comes down to how much people are willing to fight for them.”

Peter Thomson discusses Sacred Sea on November 28 at 6 pm at First Parish Church, 3 Church Street, Cambridge. Visit globecorner.com for details.