ON

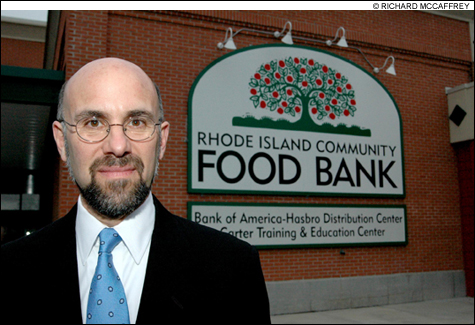

THE FRONTLINES: More than 11 percent of Rhode Islanders are hungry, a problem that keeps

Schiff and the Food Bank’s staff and volunteers very busy.

|

|

How to help:

While there are many worthy social organizations in Rhode Island, these are some of the largest umbrella groups:

Amos House

Amoshouse.com

401.272.0220

415 Friendship St.

Providence, RI 02907

The Rhode Island Community Food Bank

Rifoodbank.org

401.942.6325

200 Niantic Ave.

Providence, RI 02907

Crossroads Rhode Island

Crossroadsri.org

401.521.2255

160 Broad Ave.

Providence, RI 02903

The United Way of Rhode Island

Uwri.org

401.440.0600

229 Waterman St.

Providence, RI 02906

The Fund for Community Progress

Fundcp.org

401.941.7100

1604 Broad St.

Providence, RI 02905

|

Most of the food banks and soup kitchens across the United States emerged during the so-called Reagan recession of the early 1980s, in what was considered at the time as a temporary solution to a growing problem. Yet although the economy improved, the problem of hunger has continued to worsen, due in part to shrinking federal support, leaving a national network of volunteers, donors, and emergency providers striving to meet the need.

The Rhode Island Community Food Bank has played an important local role since it was established in 1982, distributing food to more than 150 emergency food programs across the state, including those not just in cities, but in towns and suburbs like Smithfield, Cumberland, Coventry, Barrington, Charlestown, East Greenwich, and North Kingstown.

Leading the effort is Andrew R. Schiff, previously the assistant director at Boston-based Project Bread, who succeeded longtime executive director Bernie Beaudreau in May. While the food bank has an ambitious plan to eliminate hunger in Rhode Island, it — like other social agencies — faces the fierce combination of a worsening economy, Rhode Island’s staggering budget deficit, and a widespread foreclosure crisis.

To help illustrate the ongoing problem posed by hunger, the Phoenix talked with Schiff last week in his office at the food bank’s Niantic Avenue headquarters, in the Reservoir section of Providence.

How serious is the problem of hunger in Rhode Island, and why is the problem getting worse?

It’s all about the economy. People who are caught between low wages, fixed incomes, and the high cost of living often are unable to afford adequate food. There are just more and more people in that situation. They don’t make enough, and then they can’t afford to pay their bills.

The US [Department of Agriculture] does a survey each year of the prevalence of hunger; in Rhode Island, it’s 11.3 percent of all households. So that’s 48,000 households that report being at risk for hunger, and it’s a significant increase over the last 10 years.

That’s a lot of households, and although the stereotype might be that we’re thinking about people who are homeless, in fact, we’re talking about many people who pay rent, many people who are working at low-wage jobs, and we’re talking about — as it turns out in Rhode Island — many, many people who are eligible for government benefits, but are not taking advantage of them.

What does it say to you that the problem of hunger has only grown worse since many food banks and soup kitchens were established in the early 1980s?

I think it goes back to the economy, that during the same period, the last 25 years, the jobs that have seen growth in our economy are jobs that require higher education. And without a good education, at least a solid high school education, people aren’t able to get those jobs. Meantime, the [manufacturing] jobs that were around for people who were skilled, but had not graduated from college, those jobs have disappeared.

So there are fewer and fewer opportunities overall unless we are going to be able to provide a really good education to the people right now who are our kids.

What has happened during that same period is that we have seen, as you’re saying, the institutionalization of food banks. But, really, the organizations providing the emergency food to people, the emergency food pantries and the soup kitchens — I think we have to remember that they’re still very much grassroots organizations.

There is no “system” of emergency food. It is still communities coming together, saying we really want to help people in need. And out of a church basement, almost always based on the goodwill of volunteers, we supply the food. But these community-based organizations don’t happen without local leaders.

It happens in a church, it happens in a neighborhood — that those organizations are able to pull together and help. But it’s just as possible that the volunteer who’s the head of that food pantry gets older and is no longer able to put the hours in, because it’s also very physical work, [and] the program can end, can stop. So it’s not like we have emergency rooms all over the state.

We have 150 food pantries and soup kitchens across Rhode Island, but I don’t want to give the impression that they’re at the level of an organized emergency system. So we have this charitable response to the problem of hunger that’s been relied on more and more, and I feel, stretched to capacity at this point.