CRICKET: Household creates unbearable tension by keeping his fugitive in one place.

|

Some books strike startlingly similar chords in their readers. Whenever I’ve come across someone else who’s read Geoffrey Household’s 1939 Rogue Male — just reissued by the New York Review of Books in their series of classics returned to print — neither one of us has ever talked about the book in the gleeful or excited way readers usually talk about thrillers. People who love this book tend to talk as if reading it were experiencing something terrible and necessary.

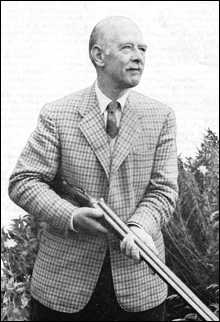

Household wasn’t a sadistic writer. By any standards (not just contemporary ones), the violence here is rendered with great discretion. Household’s unnamed protagonist is an aristocrat sportsman, and his view of the world is very much along the lines of what is and isn’t cricket. (Looking at the dust jacket photo of Household that adorned the novels he wrote in the ’70s and ’80s—snow-white mustache and fringe of hair, plaid sports coat and ascot, and affectionately holding a big marmalade cat whose tough tabby expression tells you he’d prefer to be on his own fours — it’s easy to imagine Household possessing that sense of fair play.) Rogue

Male is about trying to hold onto some sense of justice and proportion while finding the tactics to defeat a force that has no recognition, no interest, in those qualities.

The book opens in an unnamed European country (read: Germany) with the hero being found in possession of a rifle with a telescopic sight outside the country home (read: Berchtesgaden) of the country’s leader (read: Hitler). Tortured and left for dead, the anonymous hunter manages to make his way back to England, only to find that agents of the European power have pursued him. His English gentleman’s sense of responsibility will not allow him to involve the government in an international incident by seeking their protection, so he flees to a foxhole in the country.

Part of what makes Rogue Male so memorable is the oddness of its form. This is a novel of pursuit in which the pursued stays mostly in one place. Household was a great physical writer. As his hero makes his hideout, building his underground lair and covering his tracks, both he and his creator display a sensitivity to the English countryside, a sense that it will provide shelter and food and also spiritual ease. The most peaceful moments of the book are the hero’s remarking of the sound sleep he finds in some copse or the hollow of a tree.

But, at the same time, it’s about not becoming an animal, and Household writes of his solitary protagonist — by necessity separate from all human contact — as the embodiment of humanity and, by implication, the agent after him as the representative of a regime that, to borrow a line from Cyril Connolly, opposes “every reasonable conception of what life is for, every ambition of the mind or delight of the senses.”

Saying such and such a leader should be assassinated is always good for a shocked laugh, a way of proving how tough-minded you are. That World War II was certain when Household wrote Rogue Male does not lessen the moral courage of the book or its clear message that for any sense of decency or humanity to prevail, the leader of a foreign country must be assassinated. To present American readers, this may sound too much like the mindset that has mired us in Iraq. But there’s no euphemism at work in Household, no “Mission Accomplished” braggadocio. Before the talk of the good war and all that followed, Household, in this slim, moving, almost unbearably tense novel, was unwilling to let us forget that winning the good war meant putting our fingers on the trigger.