|

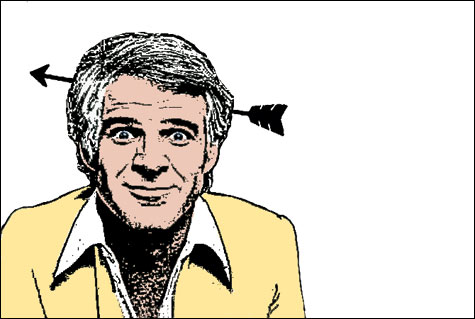

Once upon a time, way, way back in the sleazy and odoriferous 1970s, when even the most ardent amateur bombmakers of the previous decade had hung up their fuse-wire and started taking Quaaludes, there was a man in a cocaine-white three-piece suit who stood onstage with a fake arrow through his head and played the banjo. He played, to be precise, Earl Scruggs’s “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” — a tune from 1949 acknowledged by connoisseurs of the five-string banjo to be one of the more demanding workouts in the bluegrass canon. And he played it beautifully, with a silvery, ecstatic proficiency. And the tens of thousands of people who had come to see him do his stand-up comedy, to see him get his “happy feet” and shout “Well, EXCUUUUSE ME!” and tell silly stories about his cat, would be visited — for these few moments — by an unwonted solemnity. A stillness would descend upon them, a stillness that recalled the dictum of a character in GK Chesterton’s The Napoleon of Notting Hill: “Only coarse humour is received with pot-house applause. The great anecdote is received in silence, like a benediction.”

In a way — in a very abstract, theoretical, what-the-fuck-are-you-talking-about sort of a way — the eruptive and audience-silencing virtuosity of Steve Martin’s banjo-playing was the punchline to his entire act. There certainly weren’t any other punchlines. Ridiculous dancing, yes, and magic tricks that went wrong, and a delicious, steadily deepening sense of derangement, but no pay-offs or zingers or ba-BOOMs. Martin’s onstage persona was that of a profoundly deluded man who thought he was funny, who thought he was a sophisticated professional entertainer, and whose confidence in this regard was so punctually out-of-sync with reality as to suggest an entire new dimension of comic potential. He wasn’t assaulting the conventions of stand-up with quite the violence of his colleague Andy Kaufman (of whom the possibility remains that, while being a great and savage humorist, he was actually a terrible comedian), but his act was inside-out: anti-comedy, his friend Rick Moranis called it. “I just got back from my trip to Europe. I guess you could say that I saw London . . . and I saw France, and then . . . I saw someone’s underpants!” (Yelps of buffoon laughter.) So when it was time for a bit of “Foggy Mountain Breakdown,” and the gaping face of the clown grew suddenly focused and intent, and the arrow through the head trembled or the fake bunny ears nodded gravely as he ripped through his ultra-technical banjo-runs, the moment was properly greeted with a thrilled sobriety. That guy people had started to get used to — but who was this guy?

Hilarious post-Aquarius

Martin’s new memoir, Born Standing Up (Simon & Schuster), grants us our best access yet to this remote and brilliant figure — the cool architect of the comedy. “My most persistent memory of stand-up is of my mouth being in the present and my mind being in the future,” he writes on the first page. Show business, unlike life, tolerates few genuine accidents, and it should come as no surprise that the big-visaged, flapping-limbed, borderless and random-seeming exhibitionist who went by the name “Steve Martin” for a couple of hours onstage was a comic calculation that had been tested and re-tested through decades of experiment. Born in Texas in 1945 and raised in California, the young Martin served his apprenticeship in a vivid and dusty showbiz crazyworld that already seems two centuries away. His first job was in a magic shop in Disneyland; his first sexual partner was a vaudeville actress who would go on to become a million-selling author of Christian how-to books. Vintage figures stroll back and forth across the early chapters of Born Standing Up — the promoter Claude Plum, to whom Martin was briefly indentured, or the singer/comedian Martin Mull, drawling his way through Morrissey-esque numbers like “I’m Everyone I Ever Loved” and “(How Could I Not Miss) a Girl Your Size.”

As the ’60s gathered momentum, Martin wrote for TV (The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour), worked on his stand-up, got high, and suffered his first panic attack, the classic telescoping of the self into the vertical dimension: “I felt my mind being torn from its present location and lifted into the ether.” He stopped getting high. The attacks diminished, though slowly, melting away “like ice around Greenland,” and he learned something terrible about everyday life: “Now I could be funny, alert, and involved while nursing internal chaos.”

But there are gifts that come with distance, painful as it can be. Road-hardened, newly skeptical of the drug culture, and flexing paranoid powers of self-surveillance, Martin was ideally positioned — as the ’60s flopped into the ’70s — to make a zeitgeist-piercing leap with his comedy. “Around this time,” he writes in Born Standing Up, “I smelled a rat. The rat was the Age of Aquarius.” The revolution had foundered in bitterness and mysticism. Burnout was in the air; the culture had become faddish. It was time for some laughs that were post-political, post-psychedelic, even post-laughter.