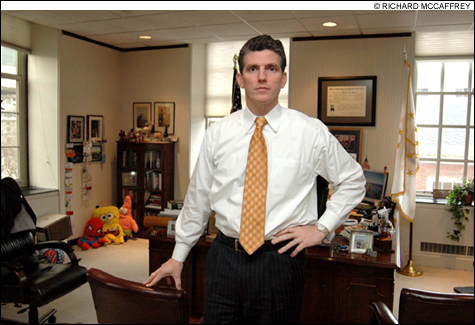

SURVIVAL SKILLS: Lynch has picked fights and pursued issues that offset some of the controversy

invariably associated with the AG’s office.

|

One small basketball photo lurks inconspicuously on a far wall in the spacious South Main Street office of Attorney General Patrick C. Lynch, a reminder of the time when the former BrownUniversity guard and his teammates overcame long odds, ending a road losing streak that had extended for more than 30 years.

“So I keep it there partly to remember that it was fun playing back then, but more so as a reminder to myself — you don’t quit, never stop,” Lynch says, referring to the picture of him sinking a shot during an upset win in 1986 at the University of Pennsyl¬vania’s Palestra, one of the hallowed halls of college basketball. “I think that’s kind of the message — we didn’t give up.”

Lynch, during a recent interview, touched on the unlikely victory in describing the need for Rhode Island’s elected officials to work together in facing the state’s dire budgetary problems, which include a projected $450 million deficit for the next fiscal year (the talk of collaboration notwithstanding, he opposes cuts in his own office, calling it a model of efficiency). Yet the hard-charging outlook also marks an apt summation of Lynch’s thinking, half-way through his second and final term, as he moves closer to his next run for office.

Making lemonade out of lemons

The conventional wisdom is that the attorney general’s office in Rhode Island is an irrefutable political dead-end. Even former AG Sheldon Whitehouse, who won a US Senate seat in 2006, had to first go through the character-building experience of losing a Democratic gubernatorial primary to Myrth York in 2002.

And to be sure, Lynch’s tenure has been marked by some of the controversial, emotionally freighted cases — particularly the legal fallout from the Station nightclub disaster in 2003 — that invariably land on the attorney general’s front door, representing potential political poison.

In New York, the example of Eliot Spitzer, who gained admirers as a crusading AG, only to experience sharp political setbacks after winning the governor’s office, offers a cautionary tale. Closer to home, the fact that William Lynch, the AG’s older brother, chairs the Rhode Island Democratic Party strikes critics as another example of how the fix is in among Democrats.

And to top it all off, there’s no paucity of potential Democratic gubernatorial candidates for 2010, including General Treasurer Frank Caprio, Providence Mayor David N. Cicilline, former lieutenant governor Charles Fogarty — who nearly beat Republican Governor Donald L. Carcieri in 2006 — and Lieutenant Governor Elizabeth Roberts, the first woman to hold such a prominent post in Rhode Island.

Yet even though Lynch, 42, offers typical boilerplate when asked whether he will pursue the top job, the AG can’t resist telegraphing the message that seems bound to accompany a forthcoming campaign.

Asked to cite his most satisfying accomplishments in office, for example, he says, “I think more of the consistent theme of fighting on to protect people, regardless of the circumstances, and that was the attraction to this job initially . . . having an opportunity to fight every day for the quality of life of Rhode Islanders.”

Going forward, Lynch will remain at the forefront of some of the state’s most high-profile issues, including efforts to find budget savings through reductions in the state’s prison population and a proposed mega-healthcare merger — of Lifespan and Care New England — that would have profound consequences for Rhode Islanders.

Yet even though Caprio and Cicilline have led the way in the early fundraising race, Lynch could be a potentially strong candidate for the governor’s office in 2010.

Part of this is due to how the AG has taken to various fights — to oppose the expansion of an LNG facility in Providence, to bury power lines running by India Point Park, and most spectacularly, to gain restitution from lead paint companies — which bolster his battling self-description and offset the less flattering news that attaches to his office.

In this respect, Lynch might be considered a local political equivalent of Survivorman, the resourceful Discovery Channel naturalist who ekes out a cheerful existence amid a spare and inhospitable wilderness.

Put another way, it’s no surprise that Lynch professes some admiration for the philosopher who posited that what doesn’t kill you just makes you stronger.

“I didn’t know I was such a fan of Nietzsche until you offered me that quote,” quips the AG, quickly resuming a mantra that makes it sound as if he’s already running, talking of “the challenges we face, and how I’ve stood strong for the people and been a leader, not only in this office, but on a host of different issues in challenging times, and I think that’s what these times call for.”

No time like the present

Democratic activist Robert Walsh, executive director of the National Education Association Rhode Island (who is unaligned in the 2010 governor’s race), notes that Lynch is in a very straightforward position: he has little to lose by running, particularly since he is the only one among the four prospective Democratic incumbents who is term-limited. “I am convinced that he’s running for governor,” says Walsh, noting that Lynch, if he were unsuccessful, could reasonably anticipate a soft landing in his former work as a lawyer or a lobbyist.

And while the ultimate field may not become clear until after the presidential election in November, Walsh believes that not all of the four most-frequently touted Democrats will wind up in the gubernatorial hunt. “I think that both Caprio and Cicilline have to look at the possibility that they would be eating into each other’s votes, to some extent,” he says, as well as an overlapping fundraising base.

Lynch, meanwhile, will enjoy heightened exposure, and an opportunity to cultivate useful contacts, when he assumes the presidency of the National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG) during a June ceremony in Providence.

Lynch will also have the chance to pursue his own presidential initiative, and considered his self-described interest in juvenile justice, don’t be surprised if he takes on something — as with Internet predators or the welter of under-age drinking incidents in Barrington — that plays well with a suburban demographic.

As it stands, Lynch’s approval rating has been better than might be expected, hitting a low ebb following the contentious resolution of criminal charges in the Station fire case. The percentage of respondents who believe Lynch is doing a good job, as measured in a survey by Brown University’s Darrell West: 48 percent (June 2005); 44 percent (September 2005); 48 percent (June 2006); 51 percent (September 2006); 40 percent (January 2007); and 48 percent (September 2007).

As one of seven children of former Paw¬tucket mayor Dennis M. Lynch, who died in November, Lynch was raised on politics. In one measure of the reach of the Lynch family in Rhode Island, the line of visitors paying respects during the patriarch’s wake extended for more than two hours.

While politics also runs in the family for Caprio, Cicilline, Fogarty, and Roberts, one unaligned Democratic observer says this about Lynch: “I think he brings an energy to the race. He clearly knows how to work a crowd. The family lineage is such that it is ingrained in him, and part of his genetic makeup, and that’s a real advantage from him.”

In the run-up to 2010, some of the potential candidates have picked off key staffers from rivals, with ace fundraiser Amy Gabarra going from Cicilline to Caprio, and adviser Ani Haroian moving from Lynch to Cicilline. For his part, Lynch buttressed his potential campaign organization in October by hiring Jeff Guimond, a former top Fogarty aide, as his director of policy and legislation, and shifting longtime aide John Palangio into a new role as his chief of staff. Lynch also has a potentially valuable staffer for outreach efforts in Latina activist Aida Crosson, his director of personnel.

The resolution of the lead paint case, in which three paint companies are appealing a state plan ordering them to spend $2.4 billion to remove lead paint from tens of thousands of Rhode Island apartments and homes, could be an even more significant wildcard in terms of the 2010 gubernatorial race.

While conservatives have disparaged Rhode Island’s litigation against lead paint manufacturers as an instance of tort lawyers run amok, Lynch — whose office reached a separate $12 million settlement with the DuPont Company — sees it quite differently, of course, hailing it as a historic agreement. (Such idealism makes for an odd juxtaposition with how he accepted campaign donations from a lawyer and a lobbyist for DuPont while negotiating the settlement.)

If the timing falls just right, and if the case is decided in Rhode Island’s favor, a lot of money with Lynch’s fingerprints upon it would be distributed statewide in the run-up to the gubernatorial race.

A measure of interpretation

Shortly before 5 pm on the day of the much-anticipated New Hampshire primary, the attorney general’s office distributed a press release announcing its introduction of legislation meant to strengthen anti-corruption efforts in Rhode Island. The timing, coming five years into Lynch’s tenure, on an afternoon when media attention was focused elsewhere, was interesting, to say the least.

Asked about the timing, Lynch basically sidesteps the question, going on to tout prosecutions launched by his office against former Lincoln town administrator Jonathan Oster, former Lincoln planning board member Robert Picerno, its role in the investigation of former state Senator John Celona, and in the revocation of the pension of former Traffic Tribunal judge Marjorie Yashar, among other cases.

What does he say to those who question why a Republican US attorney, and not the Democratic attorney general of Rhode Island, is leading the charge on Operation Dollar Bill, the ongoing probe of legislative influence-peddling?

“What do I say to that?” asks Lynch. “It’s probably a Republican you’re talking to. I think everyone I ticked off [in the above-cited cases] is a Democrat, so I’ve prosecuted numerable Democrats; do they mention that? I mean, what we do is we do our job . . . When you start looking at the work we do on a daily basis, we have a tremendous success in doing that.”

Not surprisingly, Giovanni Cicione, chairman of the Rhode Island Republican Party, offers a more critical view. “I think Patrick Lynch could have done a lot more [prosecutions] as attorney general,” says Cicione, who thinks the AG will not be immune from the traditional difficulty of running from the office. In terms of Lynch’s anti-corruption initiative coming earlier this month, Cicione says, “I think that’s a political move.” He characterizes such Democrats as Patrick and Bill Lynch as “part of the problem in this state.”

(While Cicione perceives Bill Lynch’s role as Democratic Party chairman as an advantage for Patrick Lynch, Bill Lynch says that he has “worked very hard at treating everybody equally. Since I’m the chair, that’s what I would continue to try to do.” The chairman says he would have to rethink his approach if it got to the point where he felt his familial tie compromised his professional role, but, “Up to now, I don’t think that’s been a problem.”)

Andrew Horwitz, a professor at Roger Williams University School of Law, credits Lynch with having done “quite a good job” overall as attorney general. “I think he is bright and thoughtful and works hard at being fair, and handling the criminal end of things intelligently,” Horwitz says.

In terms of why federal, rather than state authorities, have traditionally led the way in pursuing local corruption cases, Horwitz points to a variety of explanations, including how some of the federal statutes are better designed; the federal government having more resources, and the FBI being “a better investigatory tool than anything the state has;” the particular priorities of the office, and how “the criminal end of the AG’s office is quite consumed by prosecuting street crime, which is its primary obligation.”

In terms of Lynch’s recently introduced anti-corruption legislation, Horwitz says, “He could have made it more of a priority, sure,” earlier on, “But if he made it more of a priority, something else slips.”

These clashing views are typical of some of the cases that involve the AG’s office, and also of how Lynch’s own stances vary with particular issues.

The greatest example of this was the plea bargain involving the two owners of the Station nightclub in West Warwick. For many Rhode Islanders, the way the case was settled reeked of a prototypical Rhode Island lack of official straight-dealing. Yet the judge in the case also offered an explanation that was credible and well-considered.

When it comes to Lynch, the AG seemed a progressive champion — and he incurred the wrath of Roman Catholic Bishop Thomas Tobin — when he ruled that the marriages of same-sex couples who wed out-of-state should be recognized in Rhode Island (a week earlier, his sister, Pawtucket City Solicitor Margaret Lynch-Gadaleta, had married in Massachusetts her longtime partner).

Yet civil libertarians were outraged when Lynch, backing Foreign Intelligence Surveillance amendments, recently supported the role of private telephone companies to help US intelligence agencies.

Looking to 2010

The December 13 snow storm — when David Cicilline and Governor Carcieri were among those who took at least a short-term hit — shows how unexpected events can influence the future.

Meanwhile, the 2010 election is more than two years away, and beneficial timing remains the most precious quality in politics.

When Dennis Lynch died, the ProJo, in reporting on his death, noted that he had considered running for higher office after leaving the mayor’s in office in Pawtucket, but wasn’t in the right place at the right time.

The timing wasn’t there in 1991, when Bill Lynch ran against incumbent Pawtucket mayor Brian Sarault, who later served prison time for corruption.

Asked why he’s the sibling in elective office, Patrick Lynch is characteristically quick with a quip. “I’m the youngest of seven,” he says, “so I was just tenderized more by all of them. I’m a little bit thicker skinned, I’m a little bit harder skulled — probably have more scars — But I learn from all of them.”

The description about suffering bumps and bruises applies to Lynch’s time in the AG’s office as well. But as far as 2010, his greatest asset might be timing, and the reality that he’s got little to use. Or to use a basketball metaphor for the longtime jock, there’s no reason not to run and jump.