ANGELS IN AMERICA: No beating wings, but the heart of this great work thumps on.

|

Angels in America can dance on the head of a pin as easily as any other kind, as is demonstrated by Boston Theatre Works’ small-scale staging of Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer-winning, two-part “gay fantasia on national themes” (at the Calderwood Pavilion through February 10). The production is low on the work’s apocalyptic element. No seraph crashes through a New York apartment ceiling at the end of Millennium Approaches — instead, she’s revealed on a platform, the broom-bristle glimmer previously perceived through the corrugated panels of Laura C. McPherson’s set expanding into large, telescoping metal wings. But the heart of this great work thumps on. Set in the mid 1980s, when the American dream of equality and tolerance is falling apart along with several relationships, Kushner’s opus has not dated. After all, the dream continues to disintegrate: with or without otherworldly messengers, moribund Bolsheviks, and a confounding “gay plague,” the world remains a terrifying place. Moreover, Kushner’s strange layering of liberal politics and magical realism retains its power and his whip-smart human characters their hold. It is in BTW’s deft handling of these less spectacular elements that the low-budget production proves a million-dollar baby.

In some ways, the 2003 HBO Angels, directed by Mike Nichols and starring Al Pacino, Meryl Streep, and Emma Thompson as the orgasm-inducing angel, was definitive. On the other hand, that was television, and Angels, with its dizzying mix of surrealism and soap opera, is very much a work for the stage — albeit one whose author advises that its magical element should be “thoroughly amazing.” What’s amazing in this production staged by Jason Southerland and Nancy Curran Willis is how piercing Kushner’s fiery, time-specific epic, with its linked angelic allusions (from Jacob and Moroni to Bethesda and Death), remains. But to appreciate fully the plays’ ingenious mélange of love, politics, and commingled hallucination, you should commit to both Millennium Approaches and part two, Perestroika: the first is better organized and less fantastical, but it is in the crazier second that the playwright’s larger themes become manifest.

In part one, we meet the principals: AIDS-afflicted “scion of an ancient line” Prior Walter and his abandoning boyfriend, logorrheic Jewish-intellectual office temp Louis Ironson; up-and-coming Mormon Republican lawyer Joe Pitt and his troubled wife, Harper; and Joe’s mentor, passionately corrupt real-life GOP power broker and Communist hater Roy Cohn, who also has AIDS but insists he’s not gay because “homosexuals have zero clout.” As Kushner’s pithy, poetic, and visionary six-hour work progresses, the relationships are painfully rearranged, and — as in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials — the border between Earth and Heaven breaks open, raining pronouncement and plaster (though only the first comes down here).

One surprise of the BTW revival is the savvy, spontaneous performances given by several young actors you never heard of — in particular Sean Hopkins as Joe Pitt wrestling the angel of his homosexuality, Bree Elrod as the ozone-mourning, Valium-popping Harper, and Tyler Reilly as reluctant prophet Prior, chosen by a down-and-out, libidinous, and leaderless heavenly host as its repository on Earth. As the cut-and-run Louis, long on theory but short on the strength to put his whole self where his heart is, Christopher Webb at first seems bland, but his fury at both himself and the zeitgeist heats up.

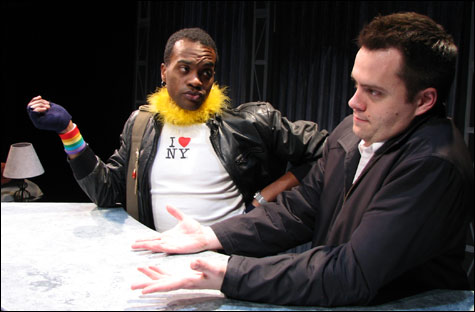

Less of a discovery but ab-fab in scrubs and a boa is Maurice Parent as cool, cocksure drag-queen-turned-registered-nurse Belize. Susanne Nitter presents a grounded Mormon mom in Hannah Pitt and a quietly gloating ghost as Ethel Rosenberg. (She’s less buyable in her turn as a rabbi bearded like the Lion King logo.) Elliot Norton Award winner Richard McElvain plays showboating incubus Cohn with a silky mix of simian gesture and smirking, explosive intensity. But the character, as written, is a yeller. As the Angel, Shakespeare & Company stalwart Elizabeth Aspenlieder is, for all the echoing effect, foxier than she is frightening. But given that she’s also earthbound, the directors come up with an effective, actor-aided plan for her inevitable wrestling match.

Harold Pinter never was an open book. Audiences and analysts have been trying to worm between his pages to pinpoint meaning ever since the 77-year-old Nobel laureate first threw Stanley his sinister birthday party 40 years ago. And to judge by A Pinter Duet, which juxtaposes the 1963 one-act The Lover with Ashes to Ashes from 1996, the playwright only grew more cryptic as time slipped by. New Repertory Theatre honcho Rick Lombardo first paired the two plays, both of which hinge on talk of adultery, at Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater in 2005. He now reprises the bill in New Rep’s Downstage black box at Arsenal Center for the Arts (through February 10), with Rachel Harker and Stephen Russell again tripping skillfully through the plays’ uneasy motions.