FORMAL DYNAMISM: Jae Ko’s Peri.

|

One of the preeminent issues of art — and, well, everything these days — is the how technology is changing our lives, making everywhere we go begin to feel like a synthetic, artificially-flavored SimCity. The issue is manifest in all the manufactured, electronic, digitally-modified, laser-cut, perfectly-finished art these days. But it also prompts craving for the one-of-a-kind, the human, the handmade, which is a driving force behind the trend of crafty art.

“Cut, Folded, Dyed & Glued: Sculpture by Imi Hwangbo and Jae Ko,” at Brown University’s Bell Gallery, reflects this desire. It presents a pair of Korean-born, US-based artists united by their crafty sculptural use of paper and their decorative designs.

Georgia’s Imi Hwangbo makes shallow paper reliefs by stacking sheets of frosty Mylar, a type of plastic film, that have been carefully printed, cut out, and layered to create blissful 3D flower and diamond honeycomb patterns, inspired in part by traditional patterned textiles made by Korean women.

Portal (2005) features three hanging sheets of cut out diamond grids that create a plaid pattern that vibrates and shifts as you move before it. Lepidoptera (2005) is a pile of sheets punctured with a regular grid of blue stylized circular flowers, all of it overlaid with a pattern of diamonds.

|

“Cut, Folded, Dyed & Glued” and “Women’s Work” Brown University’s Bell Gallery, 64 College Street, Providence | Through March 5

|

Each piece begins with a handmade drawing, which Hwangbo transforms into a computer image and prints on sheets of translucent Mylar. An algorithm calculates the recession of the pattern into the layers of paper. Then she cuts out the layers — up to 30 per work — by hand. Her meticulous craftsmanship is impressive and her patterns are initially mesmerizing; they might bring to mind decorative Islamic designs. But hers are so simple and regular, like wallpaper, that your brain soon figures them out and interest fades.

Hwangbo shifts to asymmetrical arrangements in a pair of 2007 floral designs, adding a needed formal dynamism. Sylph is a slab of irregularly overlapping red and white flowers cut out of stack of Mylar. The edges are square except at the bottom where the flowers seem to burst free of the confines of the paper. Peri looks like a tumbling garland of blue and white striped flowers. Here the flowers burst free from the paper’s square edges at both the left and bottom sides. Both pieces are thicker at the top than they are at the bottom, which gives them a cascading effect.

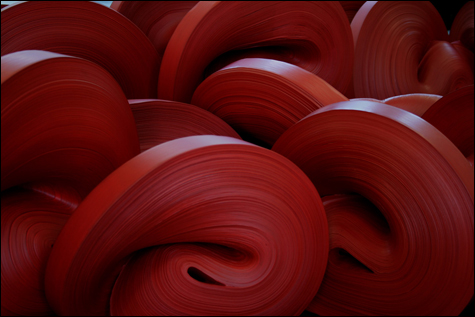

COILED: Ko’s untitled abstract shapes.

|

Maryland’s Jae Ko created two stately 2005 wall reliefs by shaping and then soaking adding machine paper in sumi ink and water, which caused the paper to swell and turned it a matte light-devouring black. The abstract forms resemble charred loaves of bread curled up on themselves and laid next to each other. Their swirling pattern recalls the stylized clouds of traditional Asian art, by way of Frank Stella’s early black stripe paintings.

Grouped on the gallery floor are Ko’s 10 spiraling coils of adding machine paper mixed with glue and red ink. Bell Gallery director Jo-Ann Conklin, who curated the exhibition, compares the abstract shapes to watch springs. They remind me of melting red train wheels and axels, or maybe dumbbells made of stretched taffy.

Hwangbo and Ko have their craft down. But for all the elegance and beauty of their technique — and maybe because the artwork is so exclusively focused on elegant and beautiful technique — the works feel empty.

The exhibition is supplemented by “Women’s Work,” a selection of 11 pieces in the gallery lobby from the Bell Gallery’s collection. Much of the art is just okay, but Providence native Lee Bontecou’s untitled 1962 wall sculpture is a knockout. It’s made of tan and green canvas (like cut up Army backpacks) stretched and wired over a welded steel frame. Menacing vents and black holes jut out from the wall, suggesting possessed mechanical eyes, mouths, surveillance cameras, and jet intakes. A large protruding hole in the center is filled with fierce saw blade teeth. It feels like a beat-up robot version of the man-eating plant Audrey Jr. from The Little Shop of Horrors. It’s angry, and strong, and scoffs at your pitiful little human concerns.