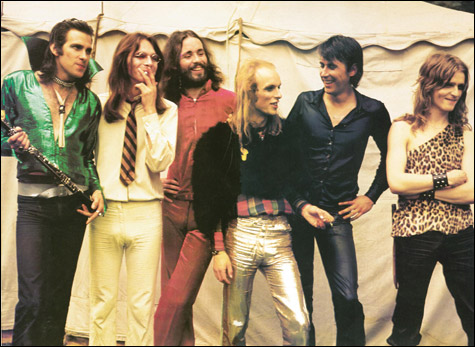

OUT THERE: Time has not blunted Roxy Music's peculiarity. |

It will probably be around page 25, when you read that Bryan Ferry was “concerned throughout his late childhood and early teenage years with the identification of those activities, individuals or ideas which might best assist with his reinvention of himself as more open to elevated, energized experience,” that you’ll start to get the feeling that Michael Bracewell’s Re-make/Re-model: Becoming Roxy Music (Da Capo) might not be your standard rock bio. Where is the teen Bryan’s fumbled first love, or the time he smoked a Chicken McNugget? The loud incompetent chords in an upstairs room? “Fuck off, Mum, I’m gonna be famous!” Not here. Here instead in the opening chapters we have a kind of compact and refrigerated bildungsroman, an æsthetic/intellectual history in which the outside world — represented by Ferry’s home town of Newcastle, England — exists only to the degree that it can be monitored in our hero’s mental fluctuations. He gets a Saturday job at a tailor’s and becomes “absorbed. . . . by the transformative qualities of fashion and style.” On page 33 he joins a cycling club, expressing thereby “a determination to transcend, and to do so with exceptional, impeccably executed panache.” And you can imagine what happens when he gets to art school (page 28).

Even now, after Greil Marcus’s Lipstick Traces and Simon Reynolds’s Rip It Up and Start Again, the rock-star-as-vector-of-ideas is still something of a challenge for us. As vector of drugs or fashion, fine; as vector of Dionysian furor, sure, why not? But to imagine him calmly processing a body of thought does something awkward to our sense of rock and roll. Nonetheless, as you goggle your way through the new Roxy Music DVD The Thrill of It All: A Visual History 1972–1982 (EMI), you might be grateful for a bit of academic guidance. What on earth could have animated these young men, in 1972, to manufacture the spectacle of a group of homosexual galactic warlords playing barbaro-industrialized lounge music? Roxy were out-there then, and they are out-there now: time has not blunted their peculiarity. Creaking fabrics, refulgent eyeliner, a fleshless sneer of grandiosity overhanging the proceedings like the Cheshire Cat’s smile turned upside down. The fact that the band members appear to be of one mind, diffusing this strangeness in a single collective exhalation, seems astonishing. What did the drummer think, thumping his way through “Editions of You” in his Tarzan singlet, as he looked over and saw Brian Eno, half-monk/half-bird-of-paradise, twisting the knobs on his “signals generator” with a silver-gloved hand?

On the unanimity of Roxy’s weirdoid-ness, Bracewell has the goods. Re-make/Re-model is the Roxy Book of Genesis, 464 pages that take us just up to 1972: the moment at which the DVD begins. They were not unique, of course, in their preoccupation with glamor, artifice, alien emissions, and so on — 1972 was also the year of Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, T Rex’s The Slider, and Alice Cooper’s School’s Out — but there was an eroticized remoteness to Roxy, an almost frigid sense of self-possession that set them apart from their stack-heeled contemporaries.

In Bracewell’s account, this derives from the cross-breeding of three complex artistic traditions: Bryan Ferry (vocals, son of a coal miner), Brian Eno (noise, son of a postman), and Andy Mackay (keyboards/saxophone, son of a gasman). As a student in the Fine Arts Department of the University of Newcastle, Ferry was tutored and mentored by Richard Hamilton, the artist sometimes described as “the English Andy Warhol,” who would go on to design the cover of the Beatles’ “White Album” (all white, as you may remember). At Ipswich Civic College, Eno got an existential retuning from a former Royal Air Force officer named Roy Ascott, whose controversial “Groundcourse” involved the destruction of received ideas including from time to time that of personality itself. (There was rather a high rate of nervous breakdown among Ascott’s students.) At Reading University, Mackay pursued what Bracewell calls a “pupillage within the avant-garde,” studying Dada and John Cage. And of course everyone was very big on Marcel Duchamp.

The role of education in the history of rock and roll has, one might reasonably argue, received insufficient emphasis. Darby Crash of the Germs attended West LA’s cult-like Innovative Program School, where a brain stew of Scientology and new-age self-actualization left him fully equipped for suicidal punk-rock messiah-hood. The seeds planted by Hamilton and Ascott, and by Mackay’s instructors at Reading, were perhaps more productive. By 1971, the young Roxys had become convinced that the proper vehicle for their ideas was not high art but pop, and so they set about creating a musical environment wherein Ferry could croon about advertising, leisure, and celebrity while Mackay’s sax slithered in circles and Eno made his emergency sonic interventions. (Bracewell has Eno playing “his stack of electronics rather as though he was bringing a light aircraft in to land in turbulent weather.”)