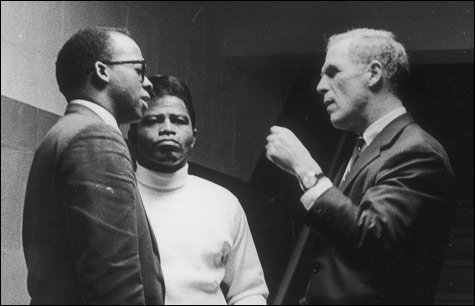

SUMMIT MEETING: Councilman Tom Atkins and Mayor Kevin White confer with JB backstage at Boston Garden.

|

Just as an attention getter, the title of VH1’s new rock-doc treatment of James Brown’s April 5, 1968, concert at Boston Garden — The Night James Brown Saved Boston — is hard to beat. But the documentary, which airs this Saturday, April 5, at 9 pm, has a much broader scope than its title would suggest. And that’s precisely why it’s so good.

Forty years ago this week, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis. The next evening, Brown played a show at the old Boston Garden, and that concert, which was televised on WGBH-TV, has been credited with helping Boston avoid the rioting that hit so many big US cities after King’s death.

The Night James Brown Saved Boston doesn’t break any new analytical ground, and that’s fine; the story itself is a good one, and eminently worth retelling. What this documentary does do is to situate the concert in a larger context. This is no mean feat, since each of the subjects lurking in the background — the cultural significance of King and his death; Brown’s own place in American and African-American culture; Boston’s ethnic and political landscape in the late ’60s — merits a documentary of its own.

But thanks to strong interviews and some expert editing, director David Leaf pulls it off. Kevin White recalls his 1968 campaign against anti-busing advocate Louise Day Hicks: “I used to kid and say, if Mrs. Hicks looked like Grace Kelly, she’d have beaten me. She was not an attractive candidate. . . . and yet she came within 12,000 votes of winning.” Ex-Bostonian Cornel West expounds on the spiritual impact of King’s assassination: “When Martin died . . . something died in black people, the very soul of black people. We haven’t got over it in 40 years.” And Al Sharpton explains the difference between Brown and artists like Sam Cooke and Nat King Cole: “Where other artists who were black . . . were able to cross over as blacks into mainstream, James Brown made mainstream cross over to black.”

The concert itself ends up getting something of a Rashomon treatment, which is as it should be. (And this 45-minute documentary is not a “concert film” — though it does make you yearn for one.) Brown wasn’t a morally pure hero: he became irate when he learned that White had arranged for WGBH to broadcast the show, and he agreed to perform only after, following some diplomatic maneuvering by then Boston city councilor Tom Atkins, the city agreed to guarantee $60,000 in projected lost revenues. Then again, he rose to the occasion by giving a great performance on an evening when he had reason to fear for his own safety — and he even prevented a possible race riot by intervening when black stage jumpers were confronted by white cops.

White wasn’t beyond criticism either. At one point, he describes Brown and himself as “two arrogant people.” What’s more, his prompting of the WGBH broadcast stemmed from a desire to keep angry black youth out of the downtown area; Cornel West wonders whether he would have done the same if the concert had been slated for a black neighborhood. On the other hand, White’s appearance at the concert itself — in which, after lauding Brown, he offered a touching tribute to King and his legacy of nonviolence — was political genius. (Given the circumstances, so was Brown’s decision to praise the mayor as a “swingin’ cat.”)

The Night James Brown Saved Boston is tinged with sad footnotes. White has been suffering from Alzheimer’s and is currently in hospital after a nasty fall; Brown died in December 2006. But together on stage before the concert that night in 1968, they’re master showmen radiating vitality and charisma. Everybody grows old, and everybody dies. Thanks to VH1’s admirable treatment, however, the memory of what Brown and White accomplished 40 years ago should endure.