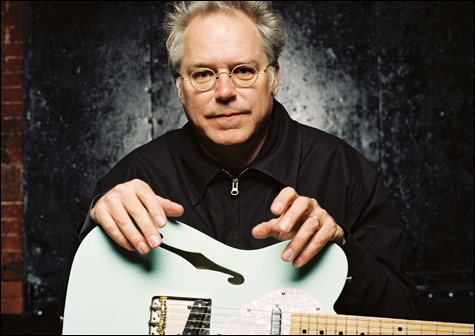

BILL FRISELL and his 858 Quartet traveled from Gerhard Richter to Charlie Christian and Marvin Gaye. |

WFNX’s Jazz Brunch Top Five

1_Bobby Watson, From the Heart [Palmetto]

2_Lionel Loueke, Karibu [Blue Note]

3_Orlando Poleo, Curate [Cacao]

4_Rupa and the April Fishes, Extraordinary Rendition [Cumbacha]

5_Travis Sullivan’s Björkestra, Enjoy! [Koch] |

Carla Bley’s local appearances are so rare that each one is an event. Her show at Scullers next Wednesday with bassist Steve Swallow and saxophonist Andy Sheppard is the first in memory since her 2005 appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival. The former enfant terrible of jazz composition is now, at 71, something of a grande dame. In the ’60s and early ’70s, her big-band pieces, her arrangements for Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra, the pieces she had earlier written for then-husband Paul Bley as well as Gary Burton, George Russell, and Jimmy Giuffre — these made her a young avant-garde star. But in the succeeding years — with all sizes and shapes of ensembles — she’s plied her own brand of jazz classicism, indebted to pop-song structures but imbued with her own quirky sense of humor and a melodic gift that seems to have been stamped on her since, as the young Carla Borg in Oakland, California, she took lessons from her piano-teacher/church-choirmaster father. That probably also explains why Bley, schooled as she is in the jazz-blues tradition, has a knack for American hymn tunes.Bley has had a long association with ECM, and last year she released The Lost Chords Find Paolo Fresu, a meeting of her quartet (including drummer Billy Drummond) with the young Italian trumpet player. The lyricism, the humor, the elusive harmonies, the off-kilter Monkish melodies are all there, and the kind of jazz writing that almost completely obscures the division between composition and improvisation. Sheppard and Fresu seem to be finishing each other’s sentences.

“That’s why I got Paolo,” Bley tells me over the phone from her home near Woodstock, New York. “Because Andy said, ‘I played with this guy and it was magical, we both played the same note.’ He had never experienced that, so I said, ‘I’m going to get Paolo for Andy, then.’ ”

In fact, Bley says there was somewhat less writing for this Lost Chords album than, for instance, on her big-band records, especially on the six-part “Banana Quintet” that takes up the first half of the disc. “I think on that piece there was a lot more improvising than usual, but it wasn’t as though the guys had a better time doing it, because it was all in series of five, and it was quite difficult.” Bley is talking not only about the use of the interval of a fifth throughout the piece (prominent in its wistful, descending opening figures) but also in the asymmetrical five-bar phrases rather than the more typical multiplications of four in standard 32-bar song forms. “It was like speaking in a strange language — for all of us. We didn’t goof off in playing the series of fives at all — we buckled down and really tried hard to feel it. It’s not evident that things are not symmetrical. And that was my hope, to disguise it and make it seem normal — but it’s not.”

That tantalizing strangeness — the asymmetrical phrasing, the odd tensions in the chords that pulse through the pieces in the voicings of Bley’s piano and Swallow’s five-string electric bass and in the way Sheppard and Fresu navigate those chord changes — belies the surface pop-song familiarity. When she writes a cyclical triple-meter melody like the album’s “Ad Infinitum,” you might wish the deceptively simple tune would go on forever.

Bley marks the turning point in her music as her association with long-time companion Swallow (who also happens to be one of the most important voices in jazz bass). “He started making me play Real Book tunes,” she says, referring to the semi-underground collection of jazz and pop-standard lead sheets that Swallow is credited with helping to create. “He taught me how to play with my left hand — accompanying myself at the piano. I used to double the bass notes or do really stupid things. And he taught me what to do over a period of about a year just playing privately in the basement of my house. That was about 20 years ago. Before that time, I didn’t know what chord changes were, even. I’m sure I wrote chord changes, but I didn’t know what they were called.”

Which is remarkable when you consider that early in her career older composers like Russell and Giuffre were adopting Bley’s work as sophisticated compositions. “It was the opposite,” she counters. “The sophistication happened with learning that conservative way of doing things. Before that, I had a wild imagination, and I wrote down a lot of things without wondering what they meant. Now, I’ve totally changed, and I think very hard about song form and specific changes and the history of music and the history of piano playing in general — who does it, what they’re doing, why they’re doing it, and how could I do it. And of course I can’t do it, but it’s fun to try.”