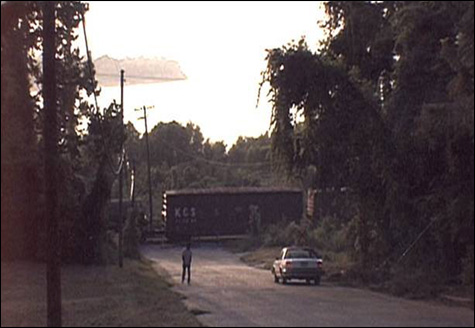

LOOK ALIVE: Akerman’s films demand an atypically active approach to viewership.

|

|

“Chantal Akerman: Moving Through Time and Space” MIT List Visual Arts Center, 20 Ames St, Cambridge : May 2–July 6

|

At the movies, you know your place. Despite lacking any overt ritualistic rigmarole, a visit to the cinema remains one of the most cooperatively ordered experiences one can have with a piece of art. (Tell that to the jerk with the Nextel down in front!) As viewers, we accept the proposed duration of our stint in the seats; the gleaming rectangle gathers our visions; the strategically plotted arc of the story guides us through the surrounding darkness; and the dawn of the credits adjourns us back into the unordered world. We know our parts more deeply than the actors we gaze upon; and though together we form a kind of narrative construction crew, we actually have very little work to do.

If those collective behaviors inspired and demanded by the cinema of its witnesses are, in essence, its very boundaries, Belgian-born filmmaker and video artist Chantal Akerman could be considered a smuggler — stealing the visual vernacular and experiential physics of the movies and repurposing them into wholly and newly spatialized forms. Sound like fun?

This week, the first museum survey exhibition of Akerman’s work comes to the MIT List Visual Arts Center, and as nondescript as the title “Moving Through Time and Space” might appear, it provides a solid theoretical foundation from which to approach the often unsure footing of her work. Conceived somewhere between the poles of the cinema and the ever-burgeoning field of video installation, her work has the benefit of many familiar canonical reference points to help you keep your bearings: the inter-subjectivity of Dan Graham, the epic structuralism of Michael Snow, the filmic portraiture of Cindy Sherman. Still, it’s Akerman’s knack for making strange our engagement with time and space (or, loosely transposed, film and visual art) that makes this collection of works a must-see.

Not to mention a must-stay.

“When you see Akerman’s films, they are demanding in a very particular way,” List curator Bill Arning tells me. “There may, for instance, be a shot that’s held long enough to lead to very uncomfortable feelings. She’s even been called violent — and yes, there is a degree to which she takes control of your time, and it is aggressive.”

Of course, Akerman’s aggression isn’t reliant on her viewers’ passivity — if anything, the works require (or, at least, deserve) an atypically active approach to viewership. The two single-channel pieces, Sud|South (1999) and Lá-bas|Down There (2006), run more than an hour each; they’ll be shown according to posted start times at 90-minute intervals. Although you certainly have the option of strolling unfettered through each one at your leisure — as you might with the multi-channel works (D’est: Au bord de la fiction|From the East: Bordering on Fiction, 1995; De l’autre côté |From the Other Side, 2002; and Femmes d’Anvers en novembre|Women of Antwerp in November, 2007), this isn’t about your leisure. The selection, arrangement, and timing of these pieces is such that the dedicated and/or curious can enjoy a meaningful experience of the entire show in three hours — and Akerman has made single films longer than that.

Apart from its own merits as a survey, “Moving Through Time and Space” serves as a worthy finale for the List’s three-part series addressing the expanding realm of video installations. Last year’s group show, “Sounding the Subject/Video Trajectories,” was an ample primer; the subsequent solo exhibition of David Claerbout explored his blurring of still photos and video. Here, Akerman’s installation work reveals not only an artist with an uncanny talent for wild (if subtle) experimentation via seemingly mainstream means but also a complete reconfiguration of the relationships among viewer, subject, and, most forwardly, medium.

What this selection does not represent (neither does it purport to) is a comprehensive examination of Akerman’s œuvre. It remains to be seen how an undertaking like that might even be accomplished.

“She’s really hard to pin down,” says Arning. “She’ll make a film that’s just a really long take of a hotel lobby, but then she’ll make a screwball comedy. One film of hers I saw [Golden Eighties, a/k/a Window Shopping] was a sort of a golden-’80s musical — all these people who look like they’re out of a Pat Benatar video, singing and dancing in a Belgian shopping mall. ”

As Arning’s paraphrased lore has it, a young Akerman got her start as a teenager: buying her own film, shooting scenes for the hell of it, and realizing, upon revisiting the development lab, that film was expensive — too expensive. The film stayed in the lab’s possession, undeveloped, for a year, until technicians alerted Akerman that it would be destroyed if she didn’t pay for processing. After she implored the lab folks at least to watch it, they did so, and one of them passed this auspicious, accidental 11-minute debut (eventually known as “Saute ma ville,” or “Blow Up My Town”) on to a friend who worked on a film program on Brussels television. Akerman’s career was born — along with a series of motifs she would keep returning to: domestic spaces, women performing repetitive tasks, and an intense focus on gestures that essayist Ivone Margulies refers to as seeming “to produce at once disarray and tidiness.”