NAISSANCE DES PIEUVRES: A compassionate study of the tortured adolescent soul. |

| The 24th Annual Boston Gay & Lesbian Film Festival | Museum of Fine Arts: May 7-18 |

Moral and ethical quibbles aside, society’s objection to queers amounts to a question of power. Mess around with the traditional family unit and the whole system could collapse. So gay cinema is by its very nature subversive, and the selection in the 24th annual Boston Gay & Lesbian Film Festival is the first in a few years to capitalize on that potential.In some instances, the subversiveness comes in a conventional package, a popular genre that itself is subverted by the filmmaker. Dominique Cardona & Laurie Albert’s FINN’S GIRL (2007; May 16 at 8:15 pm) looks at first like an above-average TV episode, a segment of Law & Order with more than the usual political content. A police detail has been assigned to protect Dr. Finn Jeffries (Brooke Johnson), head of an abortion clinic who’s been getting death threats from pro-life groups. And no wonder: not only does she kill the unborn, but she’s a lesbian who was married to another woman and is now raising an 11-year-old stepdaughter, Zelly (Maya Ritter), on her own. Her partner recently died, but that’s not punishment enough for her transgressions, even in mild-mannered Toronto, where unknown assailants take a pot shot at her as she drives home on her motorcycle.

There’s a lot going on in Finn’s Girl, much of it pretty outrageous. The detective in charge of the unit assigned to Finn is also a lesbian, so there’s another element of sexual intrigue. Zelly’s “dad” is an ambitious creep who has pushed Finn out of her laboratory, where she was trying to develop revolutionary, non-hazardous fertility methods. He wants custody of Zelly — could he be behind the shootings? Zelly herself shoplifts porn from sex shops and smokes Finn’s dope when her mom is not around, which is often. And as this family-values nightmare unfolds, the film quietly undermines all one’s narrative expectations. Finn’s Girl is well worth seeing, if only for its refreshingly unsentimental attitude toward children.

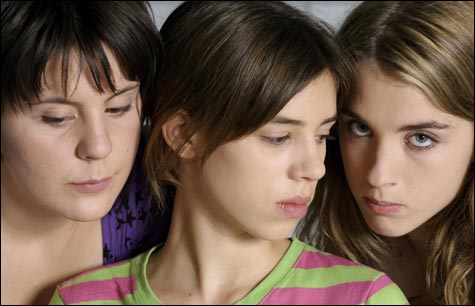

As such, it’s good preparation for Céline Sciamma’s NAISSANCE DES PIEUVRES|WATER LILIES (May 11 at 8 pm), which focuses on the teenage members of a Parisian synchronized swimming team. Marie (Pauline Acquart), a late-developing 15-year-old, longs to be one of them, so she sidles up to Floriane (Adele Haenel), the voluptuous captain of the team. Floriane is also marginalized: the other girls are envious and denounce her as a slut. Marie helps Floriane set up assignations with François, a Speedo’d hunk on the boys’ team, and this marriage of convenience deepens into intimacy. Complicating matters is Anne (Louise Blachère), Marie’s ugly-duckling friend, who has a crush on François and is jealous of Marie’s overtures to Floriane.

In short, it’s the kind of scenario that Catherine Breillat would turn into a horror story. In her feature debut, however, Sciamma serves up a detached but compassionate study of the chaotic nature of identity and sexuality as endured by the tortured adolescent soul. The girls’ relationships fluctuate in their cruelty and tenderness, achieving a kind of lyrical triumph that’s all the more touching because of their inescapable submission to the female roles to which society has consigned them.

You can’t be much more subversive than the photographer who aroused the ire of Jesse Helms and the city of Cincinnati. Which makes James Crump’s BLACK, WHITE + GREY: A PORTRAIT OF SAM WAGSTAFF AND ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE (2007; May 10 at 4:15 pm; May 15 at 4:30 pm; May 17 at noon; May 18 at 10:30 am) all the more disappointing. As a curator and collector from the ’50s to the ’80s, Wagstaff presided over one of the most convulsive periods in America art history. As a gay man, he lived through an equally loaded era in sexual politics. Robert Mapplethorpe, age 26, entered the 51-year-old Wagstaff’s life, and together they transformed Mapplethorpe into the enfant terrible of the art scene. Was their relationship exploitative? Sado-masochistic? Triumphant? No answers here: Crump reduces his subject to a ho-hum documentary as monotoned as the title, a repetitious blur of talking heads (Patti Smith comes off as boring!) and archival footage. It’s rewarding, however, for its generous helpings from Wagstaff’s stunning photography collection.

Although these movies engage with their unconventional subject matter, they do so within the conventions of traditional genre — a cop movie, a teenage sex “comedy,” a documentary. In LES CHANSONS D’AMOUR|LOVE SONGS (2007; May 17 at 8:45 pm), Christophe Honoré resorts to the musical mode to relate his tale of polymorphous desire and loss. It opens on an oh-so-Gallic ménage à trois, with Ismaël (Louis Garrel), Julie (Ludivine Sagnier), and Alice (Clotilde Hesme) sharing the same bed in what looks like a sputtering if good-humored attempt to spark the passions of the first two. The arrangement fails, of course — but in a drastically unexpected way. Alice and Julie’s Sapphic connection is snuffed out, and Ismaël, left adrift, finds comfort in unexpected places.

Chansons inevitably recalls Jacques Demy (or, more recently, Once) with its captivating score, its Jacques Brel–like tunes bouncing from one character to the next, epitomizing a mood, moment, or point of view, evoking the gaiety and grief of its gray Parisian setting. The film also brings to mind other New Wave icons, like François Truffaut, with Garrel’s Ismaël a kind of latter-day Antoine Doinel, and Erich Rohmer, with its sexual antics moored by a gossamer-light but luminous moral authority. Slight as Chansons may seem, it embodies gay — and subversive — cinema at its best.