Diary of the Dead (2008) |

In almost every movie you go to these days you’ll see another screen — a television, a computer, even another movie screen — within the screen you’re watching. Sometimes there will even be another screen inside of that screen, and so on. And often with the screen we get a keyboard or a camera or some look at whomever it is that’s behind the screen within the screen we’re looking at.

We’re not talking high-concept auteurist masterpieces like Fellini’s 8-1/2 (1963) here, either. This is happening with Bruce Willis in Live Free or Die Hard (2007) — you can’t get less pointy-headed than that. Other recent examples include Redacted, Untraceable, Cloverfield, Diary of the Dead, The Signal, Vantage Point, Be Kind Rewind, Shutter, Funny Games, even Midnight Meat Train — films that run the gamut in taste, budget, and broadness of appeal.

So it’s safe to say that all those screens and what’s behind them — in other words, the media, which includes TV, cable, MySpace, e-mail, talk radio, iPhones, iPods . . . the ways to tune in and drop out are endless — trouble the sleep of people enough for them collectively to shell out nearly 135 million bucks to watch Die Hard’s maverick cop John McClane take on this all-pervasive, multifaceted leviathan.

In 1964, when Marshall McLuhan submitted, in Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, that “We have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time. . . . We approach the final phase of the extensions of man — the technological simulation of consciousness,” it might have sounded a little over the top. Not so much now.

In this latest rash of films, just as in the White House, reality and truth are fluid, and are dictated by whoever is behind the camera.

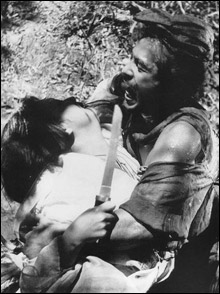

YOU CAN’T HANDLE THE TRUTH: Because in Akira Kurosawa’s classic Rashomon, there is no truth. |

Medium cruel

You’d think that an explosion in media access and technology would be a good thing as far as keeping tabs on reality. After all, don’t media by definition mediate between the user and what’s out there — other places, people, points of view? And the more advanced the medium, the closer it should get to what’s really going on. In the progression from cave paintings to photography and cinema, both long seen as windows on the “real,” the image can only have gotten clearer. As late as 1960, the great critic Siegfried Kracauer asserted that the function of film was the “redemption of reality.”Maybe he missed Akira Kurosawa’s iconic Rashomon (1950). That classic showed little faith in the search for truth, contending that even the most basic medium — oral communication — can’t get its story straight. In a medieval setting, witnesses to a crime engage in a dialectic of points of view that are mutually contradictory and reveal no truth but that there is no truth, a descent into unknowing that would henceforth be known as the Rashomon effect.

A decade and a half later, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (1966) provided another cinematic conceit for ontological futility. A photographer spots an anomaly in one of his prints. Like Kennedy-assassination conspiracy theorists probing a shot of the Grassy Knoll, he enlarges it again and again until the grains of light and darkness seem to form the figure of a corpse. He tries to confirm the evidence of his medium with proof from the real world, but human treachery, and perhaps the nature of existence itself, conspires to foil him and leave him in the state of quasi-hallucination — the post-modern human condition.

The dilemma in Blowup was solipsistic; reality can’t be perceived, not because the medium failed, but because all experience is fundamentally subjective. In Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969), the dilemma appears to be systemic; we don’t get the truth because the Man is fucking us over. At first, the protagonist, a TV cameraman, seems to be the model of objective journalism demanded by the then-vital cinema verité movement practiced, to a fault, by Richard Leacock and D.A. Pennebaker. The film opens as he and his soundman coldly record a still-breathing accident victim and then, almost as an afterthought, call for an ambulance.

Human feelings and insidious politics, however, complicate the cameraman’s ideals. He learns that the station he works for has handed over his film to an FBI investigation. But his outrage over this palls before the collective anger surging from the 1968 Democratic National Convention, which he is covering. The real Democratic National Convention, that is — Wexler shot his film in the midst of the actual events. The bloody clashes between police and demonstrators in the streets — broadcast live across the country on TV — cooperated with Wexler’s script to create one of the more amazing achievements in American cinema.