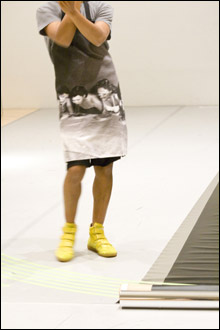

PUSH-PULL: Fusing drag-ball voguing and the Judson’s anti-dance, Harrell flaunts his body while underplaying his characters nearly to invisibility. |

Trajal Harrell's

20 Looks or Paris Is Burning at Judson Church (S) is as obscure as its title. It certainly isn't flamboyant, like the 1991 documentary film that inspired it,

Paris Is Burning, about drag balls in Harlem in the 1980s. It looks a little like the revolutionary anti-dances that took place at New York's Judson Church in the early '60s, before Harrell was born, though his performance is a great deal more calculated than those semi-improvised exercises in dance making without dancing. Harrell is acting out an imaginary meeting of the two sensibilities, and his work has a look of its own.

20 Looks or Paris Is Burning at Judson Church (S) was shown last weekend at the Institute of Contemporary Art, co-presented by Summer Stages Dance. The hour-long solo is structured as a minimalist runway show, with Harrell changing costumes on stage to create 20 subtly different "Looks" that he models for the audience. Each Look has a name, as listed on a handout Harrell distributes at the beginning. These labels are sometimes helpful. Look 15, "Eau de Jean-Michel," seems to refer to the scent of a pair of shoes Harrell sniffs but doesn't wear. Maybe they belonged to the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Other labels might mean anything. For Look 12, "Legendary," he strikes fetching poses, with his trousers half on, half off. For Look 14, "Icon," he stands in an undershirt tie-dyed in big bright splotches, holding a small baton or a piccolo crosswise in his mouth. For the only real runway number — Look 17, "Runway Performance with Face and Effects" — he wears a yellow hoodie over a black T-shirt, with a fringed black neck scarf. He struts up and down a carpet of black plastic, changing speeds and moods. He works up to an exaggeratedly angular model's walk, taunting the audience with sexy disdain. He zips up the hoodie to pull his arms tighter in to his body, then minces up and down, sultrier than ever.

Between each of the 20 Looks, he goes upstage to a makeshift dressing room, where his wardrobe of pants, T-shirts, and jackets is draped over six folding chairs. Slowly, deliberately, he pulls off one outfit and wriggles into the next. The thing is, these are all very simple, if odd, and not glamorous at all, yet he parades them in the Looks as if they were important fashions. After you take in the peculiarity of the costumes, it's Harrell himself you look at.

Harrell inhabits each of his Looks to become a different person — I thought of the powerful monologuist Anna Deavere Smith — but his technique is much less detailed and specific than hers. He's adopted the poor-boy austerity used by the Judson dancers to defy performance conventions of the time. He uses the expressive neutrality and emotionally toneless moves with which the Judson generation wanted to play down the coercive tactics of actors and dancers. But then, there's the æsthetic of display inherent in the voguing of the gay black men who frequented the Harlem balls, an artificiality that went deeper than gaudy costumes.