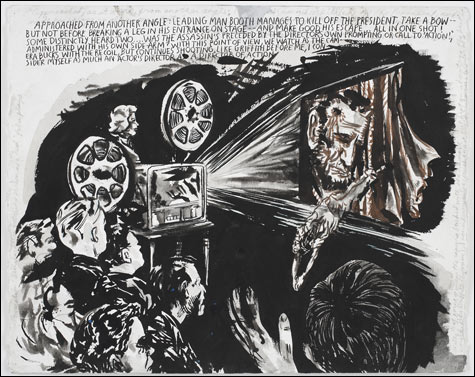

“NO TITLE (APPROACHED FROM ANOTHER)” By Raymond Pettibon, pen and ink, gouache, and graphite, 2007. |

"Was he a cynic, an enthusiast, or merely an aesthete of rough seas?"

Rhetoric scratched across a cresting wave sets the dissonant tone of "Repeater Pencil," Raymond Pettibon's 14-minute single-screen animation, which wavers between a decorated apathy and dire fatalism. A surfer trumped by the swell awkwardly careens through the frame. So begins the ambling onslaught of Pettibonisms, climbing around the parameters of time-based media, narrative continuity, and textual pragmatics to disillusioned effect — all drenched in a Southern California glow.

Pettibon, renowned for ink and watercolor drawings that develop his own spastic and cynical brand of Americana, as well as his cover art for punk/rock bands Black Flag and Sonic Youth, reveres contemporary vernaculars with the same fervor as his literary savvy and nostalgia for a '50s advertisement aesthetic. The character of his line and quick brushwork place the work initially in the square of comic or illustration, providing a levity that is quickly balanced by dark satirical subject matter and a heavy hand for saturated black washes. His subjects run the gamut of American pop culture, from JFK to film noir to surfing.

Free-associative text generally accompanies Pettibon's images, providing intentional or haphazard context. In "Repeater Pencil," action is introduced to drawings, threading a stream of familiar Pettibon motifs with repetition and an audio narration read by a motley group of voices. The voice-overs become a third interpretive variable here, but where ambiguous text successfully provokes contextualization of Pettibon's drawings, this further tilt muddies the effect and borders on wankery.

The narration sounds like a cold read. Quips "break a leg Daddy" or "not in our own backyards" are delivered with the uneasy and prosaic affectation of a high-school play reading. The sound clearly resides in an insular space other than that on the screen, one often overwhelmed by white noise. Voices are at times connected to a figure in the animated drawings, but are then reassigned, lending an even greater disjointedness to the video and further denying narrative or any real point of entry. The remoteness of the soundtrack is alienating and distracting; perhaps this is a conceit of the artist, but it is nonetheless underwhelming.

The click-click of Pettibon's repeater pencil is emphatic in imparting certain images, an arm being injected with the contents of a syringe, a moving train, a driver and passenger talking in a car, or a man with explosives — but instead of consecrating their role in a larger narrative, these images remain disconnected. They are heeded at once like meditated symbols and like the everyday signs or advertisements that rarely register in a passer-by's consciousness. Other images are more provocative or irreverent and come as pleasant interruptions. In one particularly flippant sequence a Virgin Mary exposes a breast and begins to blush a hot pink accompanied by text that reads "all eyes on her."