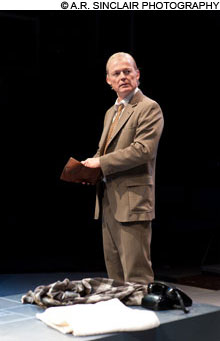

SWEET ENIGMA Allyn Burrows conquers the play’s enthused mathematical diatribes and conveys Turing’s innocent rapture. |

The heady air of MIT regularly wafts up Massachusetts Avenue and into Central Square Theater. Between the venue's joint occupants, Nora Theatre Company and Underground Railway Theater, abetted by Catalyst Collaborative@MIT, we have been offered dramas about Galileo, Einstein, Darwin, and showman physicist Richard Feynman. Now URT revives Brit playwright Hugh Whitemore's 1986 Breaking the Code (through May 8), which tells, in fragmented form, the tale of ace mathematician Alan Turing, who cracked the Nazis' Enigma code during World War II but was later prosecuted for "gross indecency" by the very state he'd helped to save. The original London and Broadway productions starred Derek Jacobi, who also starred as the stuttering emperor of I, Claudius and who can now be seen as the archbishop attending the stuttering royal of The King's Speech. The stuttering-genius role in this case is handled by the capable Allyn Burrows.

But Burrows's Turing is no grandstanding stammerer. The occasional, pained hesitation is a small if integral part of a portrayal that captures the decorated Turing's almost giddy passion for mathematics and his prophetic belief in the development of computers. Turing was also homosexual, and apparently quite naive (not unlike Oscar Wilde, who was brought down by the same law). He recklessly engineered his own downfall by admitting to a policeman investigating a minor robbery that he had committed a "crime" so patently absurd, it's hard to believe it wasn't struck from the British books until 1967. But as the play's title would have it, given the level of hypocrisy in Britain in the 1950s, Turing had broken more codes than one.

Whitemore's play, which is based on Andrew Hodges's 1983 biography Alan Turing: The Enigma, is elegantly constructed and written. It's also piquant, if a bit paint-by-numbers. Following a brief scene in a police station, we meet Turing as a boy (albeit played by Burrows throughout). Here the fervent if sensitive youth is being embarrassed by his breezily domineering mother in front of the equally precocious prep-school friend who would appear to have been his first love and lifelong inspiration. From there, the play zigzags in time, ending in 1954, after Turing has committed suicide.

Throughout his life, we learn, numbers were this brainy man's best friends. When he wasn't applying his genius to saving the nation or pursuing his other clandestine passion with a fellow engineer at Bletchley Park (where the Enigma code was cracked) or the "bit of rough" that got him in trouble, he both pioneered and evangelized for the "electronic brain" that would become our daily life support. Still, this national hero, convicted in 1952 of having had consensual sex with another man, was sentenced to a form of chemical castration. The British government finally issued an apology to Turing in 2009, 55 years after his suicide.