EARLY GLEANINGS McNeil invented Jaeger — the wanderer who connects the Finder series’ various plotlines — when she was four. |

You arrive in Anvard as an immigrant. The city is vast and perplexing, full of its own signs and codes, but little by little you learn its language. Those marks the policemen wear on their cheeks are actually psychoactive facepaint; people with the heads of animals are genetically engineered constructs with no legal rights. That lion-head woman, though, she's no construct; she belongs to the Nyima tribe from out on the plains, and the quadruped keeping pace with her is probably her son.

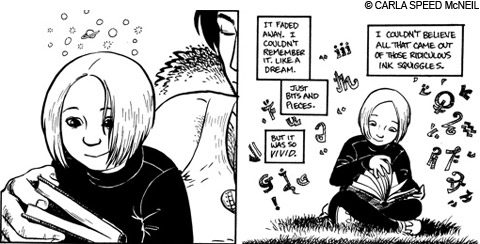

I know Anvard better than any other fictional city — better than Gotham, Minas Tirith, the Sprawl, or Ankh-Morpork. I've been learning its vocabulary for more than a decade in the pages of Carla Speed McNeil's brilliant comic book series Finder.

The series is often called an epic for its scale and scope but, unlike many fantasy series, there's no Manichean struggle between good and evil. The fate of the world is never in the balance. Instead, McNeil's characters wrestle with tribal cultural taboos, postmodern media, and old family secrets.

"The world is always ending for someone," McNeil says.

For years, McNeil self-published her comic, first under her own imprint, Light Speed Press, and then online. Now she's embarking on a run with Dark Horse Comics, which has already released a single-volume collection of Finder's first three stories, and will release a second collection in the fall.

What's more, Dark Horse will be publishing upcoming Finder stories — which McNeil says will reveal the origins of her mysterious protagonist, Jaeger, the finder for whom the series is named.

Back in the late '90s, when McNeil was still self-publishing one issue at a time, most of us discovered Finder by accident. You'd come upon an issue or two — almost never a full set — containing what seemed to be a fragment of a much larger story, like tuning in to a telenovela from Tlön. You couldn't quite tell what was going on, but the glimpse was tantalizing.

But even when you gathered the rest of the issues and read them in order, they were still confusing; the art matured quickly from good to stunning, but crucial pieces of exposition were missing. It wasn't until McNeil started issuing trade paperbacks — with extensive, explanatory footnotes at the back — that the plot of that first storyline became clear.

For years, I wondered if this was some kind of brilliant narrative experiment. McNeil, on the phone from her parents' house in Louisiana, cackles when I ask her.

"I did not know one thing about how to write a story — I mean, not one thing," she says. "And I just said, 'Well, you know, Stupid . . . you just have to start.' So I just started."