BIRTHS AND REBIRTHS Dark Matters blends Japanese puppetry and Kabuki, movie animation, shadowplay, and contemporary dance into a spectacle of porous identities. |

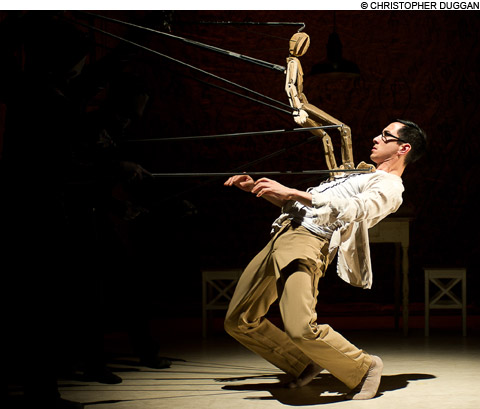

There are only seven dancers in the Frankfurt-based company Kidd Pivot, and in Dark Matters, by artistic director Crystal Pite, they slip in and out of roles, becoming manipulators and the manipulated interchangeably, until you can't trust your usual references to good guys and bad guys, builders and wreckers. The two-act drama, performed last week at Jacob's Pillow, blends the conventions of Japanese puppetry and Kabuki, movie animation, shadowplay, and contemporary dance into a spectacle of porous identities.A man sits at a table. He could be eating or drawing or doing a puzzle, but there's an almost furtive urgency to the way he goes about it. The room has been prepared by shadowy figures glimpsed in a roving spotlight. A little later you see that the man has been making a wooden rod puppet, and in the first of several shocking images, the puppet rises, a cluster of ominous black shapes looming behind it. Although the man (Peter Chu) is the creator of the puppet, once it comes to life its movements are controlled by five semi-invisible animators.

The puppet, about three feet high, is faceless, frail, and lovable at first. But it's a mischief-maker, demanding attention, refusing to be appeased, and clinging to the man's leg when he tries to leave the house. It climbs onto the table and messes up his work. The man's attempts to subdue it escalate into a fight. The puppet has the advantage, with flying kung-fu kicks and long-distance jetés. The man hacks at it with a cardboard axe and they both wind up dead, sprawled in the same position. They may be alter-egos and, though extinguished, they return in other guises.

The five puppeteer stage managers arrive to clean up. They fight amongst themselves, in a shadowplay of expressionistic slapstick that ends in disaster. The entire set collapses with a deafening crash. One stage manager creeps out and looks for bodies under the rubble. He (or she) pulls out the puppet maker and moves his limbs so that they can dance a duet together. Another search, another body pulled tenderly from under a piece of the set — then callously dumped onto the floor.

In the second half, Cindy Salgado and four men (Eric Beauchesne, Yannick Matthon, Jermaine Maurice Spivey, and Jirí Pokorný) dance in a series of groups, solos, and duets while a black-clad stage manager glides around the edges, moving large floor lamps around to highlight their action: streaking, slithering, falling, slashing, propelling themselves nearly out of control and then reversing direction to stagger backwards. By now the disjointed puppet moves have become a shared choreographic motif, part of an endless, boneless struggle. At moments, keyed by Owen Belton's action-movie sound effects, they lock together and freeze in a pose, then break apart again. The black figure slips in and out of the dancing groups, as if it wanted to become part of their choreography.