When it comes to reprobate or ostracized characters, Russell Banks has no fear. He slips eloquently into the skin of an alcoholic murderer in Affliction, terrorists in both Cloudsplitter and The Darling, a human trafficker in Continental Drift, a teenaged drug dealer in Rule of the Bone, and an incestuous father in The Sweet Hereafter. In the uneven but formidable picaresque of his latest, Lost Memory of Skin, he combines traits of the latter two characters in one that's more extreme than either — a convicted 22-year-old pedophile, the Kid.This deviant is no Humbert Humbert. He's more like Huck Finn, as Banks points out perhaps too often in the book — an un-lettered, goodhearted boy living on the fringe. Banks, narrating from the Kid's point of view in the third person, brings the boy's benighted but beguiling consciousness to life with language and syntax that evokes his voice. The convoluted run-on sentences tumble like someone falling down a flight of stairs and ending up, somehow, standing upright.

The style smoothes the way to entering the Kid's world, but it also helps that, as perps go, he isn't exactly hardcore; in fact, he's still a virgin. He's nothing like his fellow parolee the Shyster, a once-powerful politician with a taste for eight-year-olds. But he's not innocent, either. Unsatisfied with the online porn he's addicted to, he yearns, as the title suggests, to pass beyond the image to the skin itself. And so he makes the voyeur's fatal mistake, and reaches for the adolescent reality.

Busted, he serves his time, is paroled, gets fitted with an ankle bracelet, and is ordered to stay 2500 feet away from any kids. With no other options, he joins the other chomo pariahs in their shantytown under a causeway in the fictitious city of Calusa, Florida. That is, until a police raid out of The Grapes of Wrath scatters them, killing the Kid's only friend, an iguana, in the process.

That's when the Professor enters the Kid's life, another character that challenges reader empathy. Brilliant, morbidly obese, weighing in at a "quarter of a ton," he enlists the Kid in a research project studying the link between homelessness and criminal sexual behavior. He interviews him, and the Q & A provides an expository shortcut, revealing all the Kid's pathetic secrets. The Professor's secrets, though, run far deeper and defy resolution. They dominate the last third of the book.

|

Ultimately, Banks raises the question not just about media figments like the Internet replacing the reality of the skin, but also about the soul within. He also questions the value of and motivation behind such probing. Near the end of the book a "travel writer" who looks a lot like Banks himself points out that a character's secrets have significance only if he can use them in an article. Otherwise, they don't concern him. "[W]e all tell little lies," he says, "sometimes for innocent reasons. To make friends, for instance, or to avoid embarrassment. Or just to keep things simple. Sometimes the truth is too complicated to pass along in a short conversation or interview. And sometimes it's just irrelevant."Another character agrees. She should know — she's Dolores Driscoll, the driver at the wheel when the school bus plunged into a lake and killed and crippled the children in The Sweet Hereafter. Her secret is safe in this book. But both books are themselves lies of a different sort — fictions that don't conceal, but lay bare the truth.

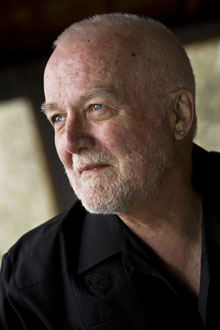

RUSSELL BANKS | Brookline Booksmith, 279 Harvard St, Brookline | October 13 @ 6 pm | 617.566.6660