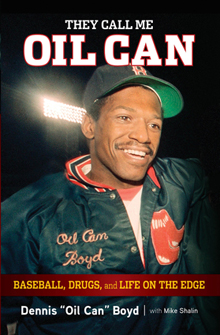

THEY CALL ME OIL CAN: BASEBALL, DRUGS, AND LIFE ON THE EDGE

BY DENNIS “OIL CAN” BOYD WITH MIKE SHALIN | REPRINTED BY ARRANGEMENT WITH TRIUMPH BOOKS | TRIUMPHBOOKS.COM | 225 PAGES | $25.95 |

Dennis "Oil Can" Boyd, a Mississippi native who lives in East Providence with his wife and two children, is one of the most complex, controversial players ever to don a Red Sox uniform. In these excerpts from his forthcoming memoir, we get a sense for the full arc of his story: from a childhood brush with Freedom Riders in the segregated South to the bitter disappointment of the loss to the New York Mets in the 1986 World Series. The writing in his memoir can be rough, emotional. But then, so is the man. Read our interview with Dennis "Oil Can" Boyd here.I'd like to begin back in 1964, in Mississippi. I was five years old — I turned six years old October 6, 1965, the same year I saw Martin Luther King in our church — but I can remember in the summer of '64, as a little-bitty boy, when these two white kids, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, and this black kid, James Chaney, came to Mississippi protesting for civil rights. They'd been all over country campaigning for civil rights, but then they came to the South, all the Southern states — Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia — and then they came to Meridian, Mississippi.

In the process of doing this they were murdered in '64, and their bodies were found two or three months later under a dam outside of Meridian, in a town called Williamsville, not too far from an Indian reservation.

At the time, we had my family — my dad, Willie Boyd Sr., better known as Skeeter; my mom, Girtharee Boyd, better known as Sweetie; and also one of my older brothers, Mike — at home. I was introduced to those three kids by my Uncle Frank, who brought them from the swimming pool in Meridian. At the time, there was segregation and we had a white swimming pool and a black swimming pool. He brought home James Chaney, the black guy, and the two white kids, who were from New York.

They were young men, I would imagine 20, 21, somewhere around there. I do remember quite well sitting in one of these white kids' lap and getting the comb caught in his hair. At the time, I didn't know what a cowlick was, or anything like that, but it was the part of the hair that was located in the middle of white kids' heads. So my mom had to cut the comb out of his hair.

After they got through visiting us they were supposed to leave and head up to Memphis. My Uncle Frank was in the car with them and my mom got him out of the car. She said, "Those boys ain't never going to be seen again and he ain't going nowhere." So Uncle Frank got out of the car, and then they left our house and they were picked up by the police and put in jail and kept there for a period of time.