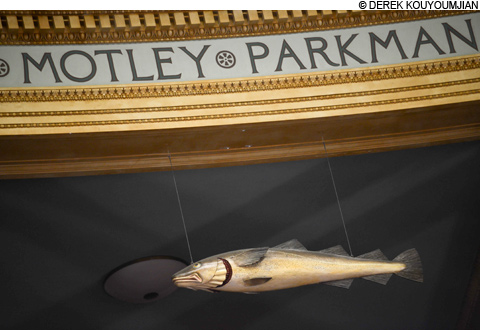

CODNAPPED: the Sacred Cod, which dates back to the Old State House, has been stolen and returned

twice; in 1933 by Harvard undergrads, and in 1968 by UMass-Boston students.

|

There have been two legendary heists at the Massachusetts State House.

The first incident was a prank, most likely pulled by drunken undergrads in white saddlebuck shoes. It was 1933; legend has it that a small crew from the Harvard Lampoon snatched the solid pine Sacred Cod from the House of Representatives chamber, smuggling the mascot out in a box fixed to look like it was holding flowers. The Codnapping shook the commonwealth and beyond — a poem titled "The Pilfered Cod" even ran in the Los Angeles Times. State police were notified, and cries of blasphemy echoed for two days, after which Harvard College Police Chief Charley Apted, acting on a tip, drove to a remote section of West Roxbury, where a group of masked men returned the wooden fish.

The second famous theft was more pro league than Ivy League. No one was ever jailed for snatching page one of the 355-year-old Massachusetts Bay Company Charter. It's said that in 1984, a man with a soft foreign accent and glasses cased the archives in the State House basement. According to investigators, another bespectacled man, about 10 years younger and mustachioed, followed up the next day by wrenching into the bronze vault holding the charter and walking out with the parchment tucked in a black leather portfolio. The burglar also swiped the wax seal that King Charles I himself had affixed to the document. The page was found six months later during an unrelated drug raid in Dorchester; the seal was recovered under similar circumstances 13 years later in Randolph. No one's ever taken credit for the job.

As the central repository for historical art and artifacts in a region with profoundly deep roots, the State House — along with the Massachusetts Archives, which moved from the State House to Dorchester in 1985 — has served as a storehouse for one of the most prized public collections of paintings and ephemera in America. More than any other state, Massachusetts has a heritage that runs deep, from the Sons of Liberty to John Singleton Copley and a host of other American masters.

But this heritage has been slowly, quietly ransacked. Over the years, countless items have disappeared — and unlike the Cod and the Charter, most have never been seen again. That includes more than a dozen oil paintings of such notables as founding father John Adams and iconic State House architect Charles Bulfinch; documents including letters from George Washington to John Hancock; a box made from the original USS Constitution; Native American arrowheads; and the marble bust of education reformer Reverend Charles Brooks, sculpted by renowned artist Thomas Crawford in 1842, which was last seen by officials in the State Library 90 years ago. In 1970, a 35-by-54-foot stained-glass ceiling — once described by the Associated Press as "one of the largest single skylights in the country" — was removed from the House chamber. It would be 17 years before anyone realized that the oval-shaped wrought-iron masterpiece was gone for good, most likely divided into sections and sold off by Beacon Hill insiders.

Appraiser Chris Barber of the Boston-based Skinner Auctioneers says the value of the missing pieces "is inextricably tied to the State House." That is to say, that without the story of where the goods came from — which could not be feasibly told, since they're stolen — they're worth no more or less than comparable works from their period. For example, few collectors would have interest in an anonymous 19th-century oil painting — unless they knew it was the missing portrait of Robert Rantoul Jr., who served in the US Senate and was a champion of religious tolerance and equal rights back in the 1830s.

The real mystery, though, is greater than each individual disappearance — it's how the commonwealth was hijacked, over the course of centuries, and for the most part in plain sight.

PERSONAL HISTORY

As a reporter in Boston for the past eight years, I've spent entire weeks at the State House working stories. While a graduate student at Boston University, I toiled in a windowless room behind the women's caucus on the fourth floor. Word was that years earlier, House Speaker Tip O'Neill sipped scotch and played cards in that room, and so I asked around to verify the rumor. In the process, I also began to dive into an ocean of much juicier secrets buried in the building's past.

Many of the stories I heard pertained to artifacts that had vanished under strange circumstances — battle flags missing in action, a magnificent 15-foot mirror taken hostage by a local businessman in the 1960s (according to legend, he offered to return it in exchange for a tax credit). People told me these anecdotes to illustrate the larcenous culture running amok in a building where the last three Speakers of the House have been indicted and a former Senate president's brother was one of America's most wanted. But I began to see that these stories added up to more than a metaphor — they were a slow-building scandal of their own.

Budget-wise, neglect is partly to blame for the gradual pilfering. For example, the Bureau of State Office Buildings, which controls the art commission, has seen its funding slashed by about $1.8 million since 2009. These are not new problems. In the Boston art heist book Stealing Rembrandts, Anthony Amore and Tom Mashberg write, "The State House in Boston once freely displayed Revolutionary and Civil War weapons and coins, and signed documents from the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony along in its corridors." In the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s, they wrote, "so many ancestral items were swiped behind the backs of unwary docents and security men" that part of the collection was removed to a secure location in Dorchester.

Cultural plunder isn't rare around here. "To put the prevalence of art theft into perspective, in Massachusetts alone, nearly every major museum in the state has fallen victim to art theft," wrote Amore, who is also the director of security at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. In some ways, the disappearance of artifacts from the State House approaches the scale of the infamous Gardner heist in 1990 — though unlike that crime, this hasn't pierced the public consciousness. While some people die bitter, having chased Rembrandts to the grave, few have acknowledged the breadth of the commonwealth's lost jewels, let alone lost sleep over a bygone canvas. And so I decided to go on a wild goose chase of my own.