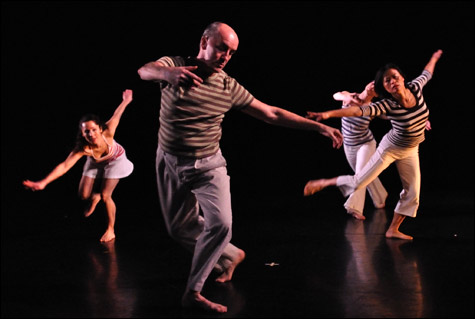

SQUINT: Brian Crabtree and Marjorie Morgan made their 13 pieces hang together. |

Two concerts last week by mid-career artists who are still looking into life's persistent questions: Brian Crabtree, Marjorie Morgan, and dancers at the Dance Complex, and David Dorfman Dance at Salem State College.

For "Squint," Crabtree and Morgan alternated pieces, 13 of them, some no longer than a minute or two, but the program hung together in style and tone. Maybe they were showing separate chapters of some larger forms they'd been working on and talking about together.

Crabtree offered a dance in four parts, for himself and one, two, or three women, mostly accompanied by the crazy-quilt recordings of North Adams duo the Books. Sharing a soft, sculptural movement language, they danced apart and together, gently touching and maneuvering around one another. At one point I thought Yenkuei Chang and Joelle Garfi might have been creatures in his dream. With Audra Carabetta, he seemed erotically involved.

Marjorie Morgan's pieces were more varied, more adventurous, but also interconnected. Morgan has been exploring the voice for a while now, sometimes incorporating singing with dancing. For this performance she composed and sang a duet in French ("Chanter Une Lettre") with Jessica Newman; then, with Newman and Allison Ball, she used what may have been the same song in a semi-canonic dance piece (Danser Une Lettre), along with some wildly assorted other musical bits.

Morgan seems fond of working around the edges of specificity. Three tiny solos were about not doing the obvious. Jim Banta caterpillared once across the space without ever standing up. Crabtree shrugged across, hands in pockets, not responding to a recorded salsa rhythm by Kaia. And Morgan mimed a bubblegum-chewing karaoke show-off who didn't sing.

Morgan opened the program with a sort of chant in a made-up vocabulary of expressive syllables. In this and all the vocal selections, she used an ordinary, unassertive singing style, as if she were doing it for her own pleasure and didn't care whether the audience understood the words. Come to think of it, that's the way everyone danced, too.

David Dorfman's Disavowal seemed just the opposite — overwhelmingly verbal, eager to communicate, accuse, uplift, change us in some way. The sprawling hour-long piece for his eight dancers encompassed a big chunk of think material about race and consciousness raising, love, learning, disagreement, play, and authority, all strewn among blocks of recuperative dancing.

Dorfman began the piece walking through the aisles, introducing the dancers with embarrassingly intimate character portraits, possibly real, possibly made up. As he exposed them, the dancers stripped to their underwear and went up on stage. Even before that, they'd proffered strands of wool to each entering audience member, color-coding us for future participation and making personal contact at the same time.

Against an intermittent background of wheeling, soaring dance-class combinations, each dancer had a solo interlude exposing his or her anxieties. They brooded about their attitudes toward their skin color. They paired off into duets featuring the depersonalized lifting and carrying moves of contact improvisation. They argued with one another, talking, screaming; they worked themselves up into tantrums, then reassembled into relative harmony again.