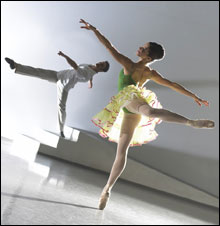

José Mateo’s Ballet Theatre, celebrating its 20th anniversary with three sets of programs by its artistic director/choreographer, has evolved an easygoing format for showing ballet work at the converted sanctuary of Cambridge Baptist Church in Harvard Square. Backdrop, wings, and theatrical lighting frame a generous dancing space, which the audience observes with casual familiarity, seated at cabaret tables amenable to drinks and chitchat.

José Mateo’s Ballet Theatre, celebrating its 20th anniversary with three sets of programs by its artistic director/choreographer, has evolved an easygoing format for showing ballet work at the converted sanctuary of Cambridge Baptist Church in Harvard Square. Backdrop, wings, and theatrical lighting frame a generous dancing space, which the audience observes with casual familiarity, seated at cabaret tables amenable to drinks and chitchat.

“Program Two” (the third set runs from April 21-30) offered three pieces in different tonalities: romantic, reflective, and playful. There were enough indications in the choreography and the music to alter the mood from one piece to another, but by the end of Friday evening, they all began to look the same to me.

Reverie (2003), set to the first two movements of Maurice Ravel’s splashy Piano Concerto in G, had a cast of three men and eight women sorted into small cadres that came and went with the swiftly passing, jazz-influenced motifs of the music. A principal couple (Desirée Reese and Sean Gunter) modeled impeccable supported poses and promenades that were echoed by two other couples. The rest of the women danced backup, but I couldn’t really say how any of the sub-groups related to one another, except when the characters were looking for a partner of the opposite sex.

This ballet demonstrated what appeared to be Mateo’s central motivation — to show off the dancers’ classical technique in clear but variable alignments. He likes to distinguish between groups with costuming. In Reverie there were four different costume designs — filmy skirts and matching tops in two color schemes for three of the women, pants and T-shirts for two of the men, biker shorts and a T for Gunter, and black tank-top unitards for the remaining women. No one is credited in the program for costume design, but these choices are neither random nor neutral.

Costumes carry a lot of information. They can cue the audience to period and place, convey the characters’ personalities, tell what work they do, spell out their rank in a fictional community or a ballet hierarchy. For Mateo, costumes serve mainly to underline his choreographically separated units, but the mixture of visual styles doesn’t help you track a larger scheme of interactions in each ballet.

By the second work, Isle of the Dead (1992), I concluded Mateo really isn’t interested in the larger implications of a choreographic throughline, or a musical one. Sergei Rachmaninoff’s 1907 symphonic poem invokes the fearful moment of crossing over from life to death. The music was inspired by the celebrated Symbolist painting of the same title by Arnold Böcklin — a tiny white figure stands over a coffin in a boat headed for the portal to an immense gloomy island of rock, cypresses, and mysterious buildings.