MUCKRAKING When Morris isn’t taking on the United States justice system or the military industrial complex, he’s extracting grand truths from exuberant weirdoes including but not limited to Joyce McKinney, the subject of Tabloid. |

The tops of the side tables in Errol Morris's office are entirely obscured by books, among them Remembering Satan: A Tragic Case of Recovered Memory; The Education of T.C. Mits: What Modern Mathematics Means to You; French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan's Écrits, and an anthology of Weekly World News stories, Going Mutant: The Bat Boy Exposed!

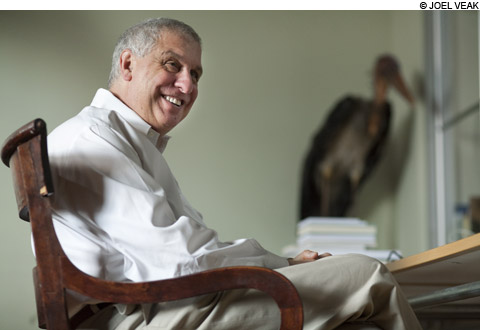

Artists' monographs — Bacon, Basquiat, Shepard Fairey — crowd an industrial shelf that stretches to the ceiling and covers the length of the wall opposite the taxidermied horse head mounted above Morris's desk. In the desk itself sits a glass dome encasing a chimpanzee head. There's a mangy marabou, too, perching in the corner.

Then there are Boris and Ivan, Morris's impossibly darling French bulldogs — live ones — who like to roll around on his Oriental rug. They flanked me proprietarily when I visited the director in Inman Square to speak with him about his latest film, Tabloid (see Peter Keough's review here).

Tabloid concerns an ultra-articulate aging beauty queen, Joyce McKinney, known to followers of the British yellow press as the woman who kidnapped the "Manacled Mormon." In 1977, McKinney followed a young missionary named Kirk Anderson from Salt Lake City to England, squired him to a cottage in Devon, and bound him to a bed. After several sex-filled days, Anderson and McKinney returned to civilization, where he promptly called the police to report that he'd been abducted and raped.

Coverage of her trial dominated the English news cycle for months. Was Joyce McKinney there to rescue her lover from the clutches of a cult-like LDS Church, or was she a harridan out to get her man at any cost? Did she rape Kirk Anderson, or did he lie to the police in order to hide his transgression from his fellow Mormons?

In addition to McKinney, Tabloid features long interviews with two rival journalists who had gone to extraordinary lengths to uncover McKinney's story. More than 30 years later, the reporters still thrill when recounting the details, sordid and otherwise.

"Somebody once said to me, early on, that Joyce is so unbelievably crazy," Morris tells me. "I said she's no more crazy than the men who are following her around in this film, myself included. These men are all obsessed."

It's easy to see why. In addition to the salacious pull of her story, McKinney herself — now in her late 60s — comes across as both charming and insane. I ask Morris what it's like to be in a room alone with her.

"You see, I have this device called the Interrotron," he responds, skirting my question by invoking his invention, which is perhaps his single greatest contribution to American cinema. Basically a jury-rigged teleprompter, it shows Morris's face on one screen, the interview subject's on another, and allows the subject eye-contact with the interviewer and the camera lens simultaneously. Morris has called the interviews he's filmed on the Interrotron "true first-person."