The good, the bad, and the brilliant

By PETER KEOUGH | November 8, 2011

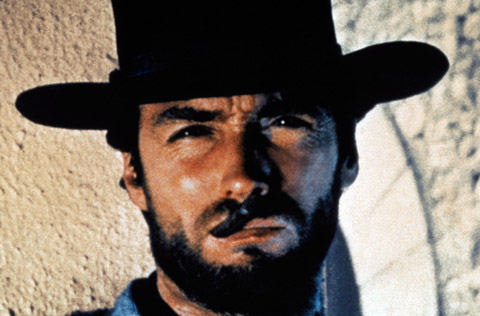

THE PRICE WAS RIGHT “This man?” Leone asked when his casting director offered a clip of Clint from Rawhide. “With a vacant look on his face, in an unwatchable film about cows?” |

He's best known for his westerns, which traditionally are sagas about how civilization begins, how ruthless and cynical men rip it out of the throat of the wilderness. But the end of civilization is what really fascinated Sergio Leone, and the poison within that undoes every would-be paradise. Death and doom and dark hilarity overshadow his films, not just the westerns, but all of them, which are on view this month in a two-week retrospective at the Harvard Film Archive. From his first directorial effort, THE COLOSSUS OF RHODES (1961; screens November 13 at 4:30 pm), to the script about the 900-day siege of Leningrad that he left behind when he died in 1989 at the age of 60, Sergio Leone showed us how the world ends — be it by the slow brutal murder of a modern city, or the catastrophic destruction of an ancient one.

DO YOU LIKE GLADIATOR MOVIES, SERGIO?

That's where Leone's directing career started, back in Rhodes in 280 BC, or rather on that set in Rome's Cinecittà studio. In style and content, The Colossus of Rhodes looks a lot like the sword-and-sandal epics that were then the bread and butter of the Italian film industry. With some differences.

The theme of trouble in paradise, for example. It starts with Athenian war hero Darius (Rory Calhoun) visiting the Eden-like title island for a little down time. No such luck. On his first day there, assassins try to kill the king — twice — and a rebel group asks Darius to help their cause. Meanwhile, the king's most trusted advisor plots to take over. Looming over all is the eponymous monolith, a 300-foot-tall bronze statue of Apollo standing astride the harbor, equipped with the third-century BC equivalent of weapons of mass destruction.

Another difference in Leone's film is that it doesn't look like the average "Peplum" (the official name for the genre, after the Greek word for "tunic"). Take the Colossus itself. Leone almost transforms the big guy into a character, with shots of it dwarfing the pitiful humans. Especially its immense feet, the origin perhaps of the many foot and foot-level shots in Leone's subsequent films, and a motif turned into a fetish by Leone's fan and follower, Quentin Tarantino. In one brilliant sequence that recalls the Mt. Rushmore scene in Hitchcock's North by Northwest (1959), the Colossus becomes a battlefield as Darius seeks refuge on its shoulder, where he battles soldiers who crawl out of an ear like ants in some lost movie by Buñuel.

BEATING SWORDS INTO SIX GUNSNot bad for a first film, but hardly the stuff of legends. Plus, the sword-and-sandal formula by then was getting a little down at the heels. The hot trend was the so-called spaghetti western, fast and dirty oaters shot in Spain and Italy with mostly Italian casts and the occasional Hollywood name looking for a check and a holiday in Europe.

Related

Related:

Review: Contraband, All's well that is Welles, Review: The Turin Horse, More

- Review: Contraband

True to its name, this standard heist thriller is a composite of knock-offs, but when Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in America is among the sources ripped off, the quality is pretty high.

- All's well that is Welles

Some of the best of the last Orson Welles flicks at the HFA

- Review: The Turin Horse

Legend has it that in Turin, Friedrich Nietzsche came across a horse being beaten by its driver. Nietzsche embraced the horse, went insane, and remained so for the rest of his life.

- Burden of dreams

As the title of Siegfried Kracauer's landmark book From Caligari to Hitler puts it, the politically shaky, culturally fertile Weimar Republic lasted roughly from Robert Wiene's nightmarish Expressionist allegory The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to the establishment of the all too real Third Reich in 1933.

- Buñuel continues to delight, confound, and shock

Openly, contentedly delighted with how our own dreams can appall us, and how close movies are to that appalling dreaminess, Luis Buñuel — the subject of an extensive survey at the HFA this month — may have been the greatest filmmaker of the medium's first century.

- Review: Aurora

Long after such an insight might do any good, Viorel, the mopey, truculent antihero of this second film in Cristi Puiu's "Six Stories from the Outskirts of Bucharest" observes that the justice system does not comprehend the complexity of his relationship to his wife.

- Review: The American

Why so many movies this year about aging secret agents? Probably to accommodate all the aging lead actors.

- Hanging with The Hurt Locker

Whatever happens at that other film awards gala in Hollywood next month, The Hurt Locker solidified its hold on indie-minded critics this past weekend when it dominated the Boston Society of Film Critics (BSFC) third annual awards dinner. That film's star, Jeremy Renner, was on hand at the Brattle Theatre on Saturday night to accept his Best Actor award, which the BSFC announced back in December.

- Sweet smell of skill

Alexander Mackendrick, who's the subject of a tribute at the Harvard Film Archive this weekend, is a somewhat mysterious figure in movie history.

- Review: Dreileben

Taking a cue from Kieslowski's Three Colors by way of the British Red Riding series, this TV trilogy from three German directors of the Berlin School starts out with a creepy aura of dread and mystery and ends with contrived and unsatisfying resolutions.

- Review: The Devil Inside

William Brent Bell's film opens with a disclaimer that "the Vatican does not endorse this movie." No kidding — the Catholic Church isn't exactly known for its sense of humor.

- Less

Topics

Topics:

Features

, Sergio Leone, film, Harvard Film Archive, More  , Sergio Leone, film, Harvard Film Archive, HFA, For a Few Dollars More, Once upon a Time in America, Less

, Sergio Leone, film, Harvard Film Archive, HFA, For a Few Dollars More, Once upon a Time in America, Less