CREMASTER 1 |

Now that we know something of the visions, allusions, and conceits behind Matthew Barney's Cremaster Cycle, it's important to acknowledge that you will, in all likelihood, scarcely be able to juggle all of its metaphors as the nearly seven-hour epic unfurls. This art-world novice spent most of his marathon screening barely moving on from an extensive game of "Spot That Reproductive Organ," as far as decoding its symbolism goes. So let's forget about its conceptual merits for a while, because while The Cremaster Cycle is undeniably a textbook example of the barely scrutable piece of video art, it is also a thoroughly cinematic experience.

But/so, are they good movies? I'll give you five answers, in sequential (if scatologically descending) order: no, god yes, yes!, only after it's over, and sort of but not really. The success of each Cremaster film basically correlates with Matthew Barney's experience and confidence behind the camera, which grows in leaps and bounds from Cremaster 1 and 4 (from 1995 and 1994, respectively) to the operatic bombast of the three-hour Cremaster 3 (2002).

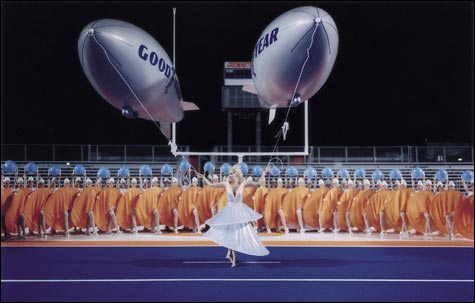

Cremaster 1 is the most technically and symbolically rudimentary of the five films, but it's a crucial introduction to the basic visual vocabulary of the Cycle. In it, two Goodyear blimps hang over the blue Astroturf football field of former-athlete Barney's hometown of Boise, Idaho. On the field, dancers with creepy plastic smiles (à la David Lynch fantasies from Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire) gather in varying formations representing female reproductive organs; above, bored stewardesses smoke and mill about the two blimp cabins, identical save for the color of grapes that fill a table; in a womblike space under the table, a bombshell writhes in her constricted space, yanking grapes down from above her, which then fall out through the heel of her shoe in formations mirroring the action on the football field (you'll chuckle at the very early CGI). The soundtrack is a mundane din on the blimp, and a jaunty orchestral score on the field.READ: "Cinematic excess: Matthew Barney’s seven-hour Cremaster Cycle descends in the Portland Museum of Art" by Annie Larmon

The problem with the short (40-minute) piece, apart from that barely anything happens, is that its bold colors and arresting visuals are undercut by a student filmmaker's sense of framing and timing. The cross-cutting is choppy and random, the sound editing is worse, and the theoretical magnificence of the dancers on the football field is hampered by the limited shot selection used to explore this space.

CREMASTER 2 |

Cremaster 2 (1999), on the other hand, is an atmospheric, dimly lit, and barely coherent stunner. Not that you'll get it, but the plot connects Gary Gilmore's 1977 murder of a gas station attendant to a covered-in-bees Johnny Cash (who, as played by Morbid Angel singer Steve Tucker, called Gilmore on the night of his execution) to Harry Houdini, who, as played by Norman Mailer(!), may have been Gilmore's grandfather.

None of this is terribly important, because it's all awesomely portrayed. Dig Barney, playing Gilmore and looking like an eyeless Ted Kaczynski, spends untold minutes stuck in an (again, womblike) vehicle at a gas station, molding something out of Vaseline(/semen) before murdering a poor attendant named Max. Bask in the stunning execution sequence where horses and, later, buffalo reenact the exercise in formation Cremaster 1's dancers did, this time in an Arctic landscape (dig that cloud cervix!) guided by Mounties and American police, in the midst of which Barney rides a bull. Watch the severe Victorian-seeming woman in a black veil ask Mailer-as-Houdini, "How did you fare tonight . . . with your metamorphosis?" The soundtrack throughout shifts from horror-movie organ music to the bustle of bees to a country two-step. Cremaster 2 proceeds with the logic and hallucinatory vividness of a fever dream.