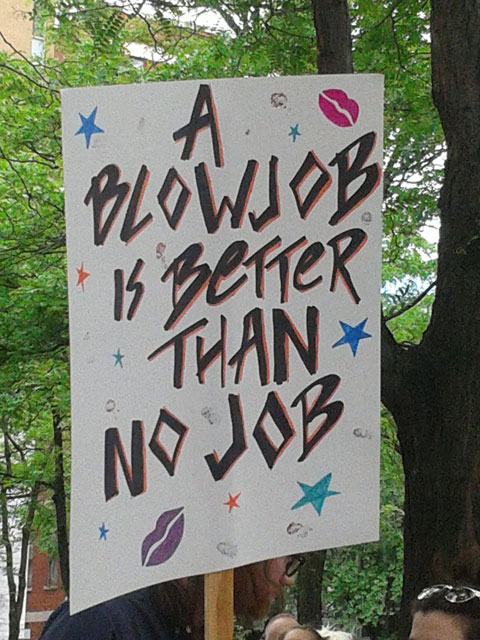

A NEW SLOGAN Another sign from the June 14 protest in Canada. |

From massage parlors offering sexual services in Waterville to a wide range of escort services operating out of Sidney, Gorham, Kennebunk, and Augusta to the regular presence of street workers in particular Portland neighborhoods, it’s clear that sex work takes place in Maine. But public conversations about this issue typically revolve around the same salacious and misinformed tropes. In recent months, we’ve seen local politicians like Republican Governor Paul LePage and state representative Amy Volk (R-Scarborough), as well as victims’ rights groups like the Greater Portland Coalition Against Sex Trafficking and Exploitation, conflate all commercial sex with human trafficking.

Meanwhile, just north of the border, Canada is taking a much different approach to policymaking around commercial sex and preventing the trafficking of vulnerable women and children. While Maine politicians, law enforcement officials, and social service agencies seem resistan t to anything other than outright prohibition, more progressive thinkers should consider other ways of looking at this unnecessarily controversial issue.

In a historic decision last December, the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously struck down all federal laws that criminalized sex work in that country. The decision came after a court challenge by three women, Terri-Jean Bedford, Amy Lebovitch, and Valerie Scott, all current or former sex workers. The women argued that Canadian laws regulating sex work were unconstitutional, overly broad, and created a dangerous work environment for sex workers by driving them underground.

The act of selling and purchasing sex in Canada was never actually illegal. Laws regulating the selling of sex have existed since the early 1800s in Canada, imported from colonial Britain. Last year’s decision, Canada v. Bedford , overturned three key restrictions related to prostitution; before the Bedford decision, it was illegal to: live off the profits of sex work (pimping), communicate in public for the purpose of sex work, and keep or work in a common bawdy house (brothel).

“Parliament has the power to regulate against nuisances, but not at the cost of the health, safety, and lives of prostitutes,” Canadian Supreme Court chief justice Beverley McLachlin wrote in the decision, indicating that what was at stake was the right of sex workers to work in relative safety, comparative to other kinds of jobs, without undue government interference. In short, Canada’s decision reinforced that sex workers have constitutional rights like everyone else. The Bedford decision continues, “The prohibitions at issue do not merely impose conditions on how prostitutes operate. They go a critical step further, by imposing dangerous conditions on prostitution; they prevent people engaged in a risky — but legal — activity from taking steps to protect themselves from the risk.”

In order to prevent an unregulated commercial sex industry from taking shape in the aftermath of this decision, the Canadian Supreme Court suspended its decision for a year in order to give its government time to craft a regulatory system that does not infringe upon the constitutional rights of sex workers. Despite this, numerous provinces (Ontario, Alberta, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador) have already signaled that they will stop prosecuting sex-work related charges except in cases of trafficking, coercion, and underage workers. “Trafficking,” as defined by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (Canada’s FBI), “involves the recruitment, transportation or harboring of persons for the purpose of exploitation (typically in the sex industry or for forced labor).”