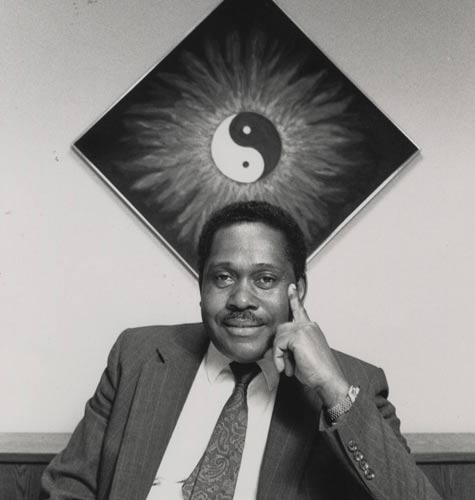

Wilson Henderson, (former) director of the Massachusetts Housing Finance Agency |

This article originally appeared in the Boston Phoenix on May 5, 1989

After more than a decade in the business, the real-estate agent knew that many landlords had very narrow ideas about whom they did and didn't want living in their apartments and houses. Most of them were fairly subtle about it. "I want the right people," they might say, being careful to couch their instructions in innocuous-sounding terms.

This guy, however, was right up front. He had a single-family house on a quiet residential street in Brighton to rent, and he wanted to make sure the broker knew just what kind of tenants he was looking for.

"I don't want," he ordered, "nobody dark."

The day he was told that, the real-estate agent nodded numbly and mumbled that he understood. Then he did what he always does: "I just agree with him and try not to bring any black people over."

So when a young white woman called and said she and her boyfriend wanted to see the house, the broker was pleased. He thought she would make an ideal tenant, and he arranged an appointment with the landlord. Eventually, the couple would see the house and like it so much that they would fill out an application on the spot. But the deal was doomed from the moment the couple showed up at the house for a tour. The woman's boyfriend was black.

An hour after the couple visited the house, the landlord called the broker and told him to cancel the listing. His brother-in-law, it seemed, had decided to rent the place.

***

More than two decades after Congress passed the first federal fair-housing laws, some real-estate brokers and housing officials say incidents such as that are still more the rule than the exception. And despite efforts to shed the reputation of racial hostility that has long plagued the Boston area, housing in and around the city remains starkly segregated, divvied up into worlds of the white and non-white – and not just in places that have traditionally been seen as white-only enclaves.

"What Southie and Charlestown verbalize," notes one former city official, "the rest of the city thinks."

This segregation is partly a product of choice, as many blacks and Hispanics prefer to live in communities of color because of either social convenience, fear of racial hostility elsewhere, or both. The perception that housing costs are higher in predominantly white neighborhoods (which is not always the case) also plays a role.

But for those members of the minority community who do decide to move into white neighborhoods, a deeply rooted and highly efficient system of racial discrimination will, more often than not, try to keep them out. Born in bigotry, fueled by fears that blacks will be unwelcome in white neighborhoods, and perpetuated by real-estate professionals who say they either "play ball or&ldots;don't do any business," that system is sophisticated and subtle, and too often goes unnoticed and unchallenged.

*On Beacon Hill, for instance, city officials investigating fair-housing complaints discover brokers who keep separate books – one for clients who will rent to minorities, another for those who won't.