The families of mentally retarded Bay Staters fight to save Fernald — and an entire way of life

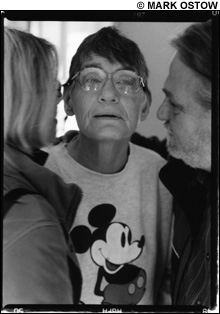

This Friday, February 24, is Margaret Rouleau’s 77th birthday. It will mark the 56th year she has lived at the Fernald Developmental Center in Waltham, a state-run facility for people with developmental disabilities and mental retardation. Rouleau is severely mentally disabled; she also suffers from diabetes and scoliosis, is blind in one eye and deaf in one ear, and has survived breast cancer. But she loves music and has a strict work ethic; when we meet one Tuesday morning in February, she informs me several times that she really has to get back to her job at a Fernald workshop, where she and other residents are contracted to assemble health-care kits for the state Department of Public Health.

This Friday, February 24, is Margaret Rouleau’s 77th birthday. It will mark the 56th year she has lived at the Fernald Developmental Center in Waltham, a state-run facility for people with developmental disabilities and mental retardation. Rouleau is severely mentally disabled; she also suffers from diabetes and scoliosis, is blind in one eye and deaf in one ear, and has survived breast cancer. But she loves music and has a strict work ethic; when we meet one Tuesday morning in February, she informs me several times that she really has to get back to her job at a Fernald workshop, where she and other residents are contracted to assemble health-care kits for the state Department of Public Health.

Since she was 19 years old Rouleau’s life has been one of routine, which has enabled her to enjoy her days, learn job skills, and contribute to the world economically. But today, she is one of 198 remaining Fernald residents whose futures are uncertain, because if Governor Mitt Romney (along with some state officials, and a sizable group of disability advocates) has his way, her home will be shut down.

Dorothy Rouleau, Margaret’s sister, is energetic and chipper, but when conversation turns to the subject of Margaret’s possible move, she sobers. This is Margaret’s home, she says, and anywhere else the state might place her would act merely as four walls. “They can’t take them from a home and put them in a shelter.” Dorothy says. “This home is full of love.”

Rouleau might not be able to stand up for herself, but a group of fiery activists is making sure that Fernald doesn’t go down without a fight.

At stake is not only the future of these individual souls who have grown accustomed to Fernald and call it home, but the future of the state-institutional system that has stretched and improved over time to treat cases like theirs.

ADVERTISEMENT

|

Critics contend that smaller-scale, community-based care fosters independence, social acceptance of disabilities, and medical innovation. But Fernald residents and their guardians fear that the greater flexibility of that model, combined with the initially jarring transition out of institutional care, would leave disabled citizens floundering without the continuity and individualized care they need.

Checkered past

The Fernald Center, founded in 1848, is the oldest institution of its kind in the Western Hemisphere, and its history is as checkered as it is long.

The center was established as a state school for the retarded, and at its peak, in the 1960s and ’70s, more than 2000 “state boys” and “state girls” lived on its 196-acre grounds — a number that has dwindled to 198 today.

For much of the 20th century, many Fernald residents endured terrible conditions — questionable “treatment” techniques, forced labor, abuse, and neglect. One former Fernald resident, 65-year-old Sybil Feldman, recalls that when she would experience muscle spasms as a teenage girl — the result of her cerebral palsy — “they immediately tied me to my bed. They would also leave me on the floor tied up for hours.” Michael D’Antonio’s The State Boys Rebellion (Simon & Schuster, 2004) describes school riots among mentally and physically sound boys trapped at Fernald in the 1950s. Other accounts describe children drinking from toilets, unmarked gravesites, and patients being used in medical experiments.

But all of that changed in 1972 when a federal class-action lawsuit led to 20 years of reform in all state-run facilities for mentally retarded citizens. Presiding over the suit against the state, US District Judge Joseph Tauro took control of these institutions, overseeing dramatic increases in funding and subsequent changes in conditions. By 1993, Tauro was largely satisfied with the improvements and issued an order that closed the case, while assuring residents and their guardians a lifetime of “equal or better care.”

Within the first two months of his administration, in February 2003, Romney announced plans to close all six of the state’s institutions for the mentally retarded, of which Fernald is one. Residents, according to the plan, would be moved into community-based care — either small group homes of about six people (usually with 24-hour support staff) or “supported living,” where a disabled person lives in a house or an apartment and, depending on his or her condition, receives varying levels of staff-provided care in or outside the home. Backed by proponents of deinstitutionalization, the governor claims that community-based care is both cheaper (running Fernald cost the state $40.5 million in 2005) and preferable for developmentally disabled citizens.