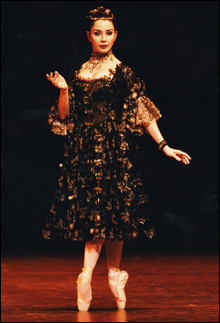

TAMARA ROJO: Big eyes, big arches, no amorality. |

Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon is Romeo and Juliet’s ugly stepsister. In place of the noble couple from Verona and their feuding but well-meaning families, we get Des Grieux, a poor student, and Manon, a young girl torn between love and money, plus her brother, Lescaut, who pimps her off, and Monsieur G.M., whose mistress she becomes, and Lescaut’s red-wigged mistress, whom Lescaut also pimps off, so peripheral she doesn’t even have a name. Based on the Abbé Prévost’s 1731 novel Manon Lescaut and choreographed to an amalgam of pieces by Jules Massenet (but none from his opera Manon), the ballet is set in Paris and, after Manon is deported, Louisiana, but it all looks like Hogarth’s England, a battleground between rich and poor, cavaliers and cutpurses, pimps and prostitutes, rakes and ratcatchers. It’s the World According to Ken, and he’s not a happy camper.MacMillan created Manon for the Royal Ballet in 1974, eight years after Romeo; sans Shakespeare’s lambent idealism or Nureyev and Fonteyn, it got a mixed reception, and though it’s entered the repertoire of the Kirov, the Paris Opéra Ballet, and American Ballet Theatre, it had never been to Boston till the Royal brought it to the Wang Theatre last week for four performances under the auspices of the Wang Center and the Bank of America Celebrity Series. MacMillan gets straight to the point: Lescaut introduces his mistress to G.M., and when she turns to greet another less-well-heeled admirer, he slaps her and then drags her over to watch a tumbrel of prostitutes being trundled off to prison, her fate if she doesn’t shape up. G.M., fresh out of Tom Jones or Barry Lyndon, makes Old Capulet seem as villainous as Daddy Warbucks, especially when he feels up Manon’s leg as if contemplating a bid for Barbaro. (There’s a lot of sexual fetishism here involving feet and legs but, rape aside, hardly any sex.) At its best, in the second-act soirée at “Madame’s hôtel particulier,” the ballet shows us Manon’s transition from Juliet-like innocence to the understanding that without money she’ll wind up like Dumas’s Camille or Verdi’s Violetta or Puccini’s Mimi. Those heroines, however, didn’t prompt their poor boyfriends to remedy their situation by cheating at cards. And the Louisiana-set third act is all masochism and maudlin melodrama, its abject women reduced to sexual slavery — not that they were much better off back in Paris.

Romeo and Juliet, moreover, has a lucid story line, if only because we’ve all read or seen the play. Manon is a muddle — as Arlene Croce said of MacMillan’s Mayerling, “Synopsis presides.” The curtain rises on “the courtyard of an inn near Paris,” one that’s “frequented by actresses, gentlemen, and the demi-monde from Paris” who, it would seem, have nothing to interest them in town. Manon, we’re told, is on her way to enter a convent; you’d never know. Neither is it apparent in the first bedroom scene that what Des Grieux is writing is a letter to his father asking for money (maybe he could sell his towering canopied fourposter, which Juliet might envy), or that Manon is deported to Louisiana because G.M. has had her arrested as a prostitute. The program provided for these performances confuses as well as clarifies: Manon doesn’t steal the Old Gentleman’s money so much as appropriate it, and Lescaut is not killed “in the ensuing struggle” after Manon’s arrest — handcuffed, he’s simply executed.

Absent plot and character, much of the ballet looks generic and recycled. Over here we have the ragpickers and ragamuffins led by that lovable rapscallion Beggar Chief, all looking for the next treat — or trick. Over there it’s MacMillan’s ubiquitous International League of Frizzy-Haired Whores, though there’s hardly a woman in the production who doesn’t hitch up her skirt to show she’s for sale. In the middle, two ladies who’ve already fallen out over a john try to one-up each other à la the Cinderella stepsisters. Everywhere we have folks breaking into Broadway-chorus-like high jinks, as if they were on display in the Manon theme park, or preparing for Manon: The Musical. Anchored in MacMillan’s Baroque inversions and Kama Sutra lifts, the two bedroom scenes for Manon and Des Grieux mirror those in Romeo, one before the first crisis (Romeo’s banishment, Des Grieux’s exposure), one after.

The score, assembled by Leighton Lucas and Hilda Gaunt (and at the Wang played for all it’s worth by a local orchestra under Martin Yates), opens on a few bars of Berlioz-like religioso chords before moving on to what sounds uncannily like H.M.S. Pinafore’s “Buttercup,” and from there it’s a kitchen sink. There are adumbrations of Bernard Herrmann in the courtyard pas de deux between Manon and Des Grieux; the first bedroom scene climaxes with schmaltz that would make Sigmund Romberg blush. The Nocturne from Massenet’s La Navarraise anticipates the Arabian-flavored “Coffee” from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker as it grounds a long, slow, hypnotic saraband, Manon being passed from one man to the next while you wonder whether they’re just admirers or whether G.M. is now pimping her out. And there’s Bette Davis five-hanky music (Dark Victory? Now, Voyager?) for the big finish as Manon and Des Grieux hallucinate amid the mist and the Spanish moss.