|

Last summer, Los AngelesTimes dance critic Lewis Segal suggested that ballet is dying an ugly, boring death. As always with this sort of thing, sides were taken, battle lines were drawn, letters and counterpoint articles were written. The take-home, however, shouldn’t be that in these times of iPhones and astro-diapers the tale of a half-swan/half-woman can’t be relevant — if that were true, we’d be throwing La bohème, Hamlet, and Great Expectations out the window as well. And yet, there is a problem with ballet these days: too many companies presenting mediocre dances and dancers.

Which is why the US debut at Jacob’s Pillow of the Swiss company Ballet du Grand Théâtre de Genève was such an unexpected gift. Neither of the two pieces BGTG performed, Japanese choreographer Saburo Teshigawara’s Para-Dice and Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s Loin, was classical, and I did hear one woman in the parking lot complain that when a company has the word “ballet” in its title, there should be ballet. But symphony orchestras present new compositions alongside centuries-old works, and ballet companies have to do the same.

BGTG comprises a broad range of ethnicities and heights — no cookie-cutter corps de ballet here — and yet this is true ensemble dancing. Para-Dice is a paean to air — its currents in the world as well as the breath inside us — and the eight dancers project this most abstract of concepts. The women’s swooping undulations in their backs seem a soft antithesis to the sharp contractions of Martha Graham. The exploration of air became an exploration of space, and then, perhaps inevitably, of time. Ferried by the now pulsating, now ambient “sound creation” of Willi Bopp, the men cut through space with vigor and purpose, or the dancers lie down one by one. Women walk forward, as if in a trance, then fall into the arms of the men, who fluidly pull them backward. The sequence is repeated again and again, and it looks deliriously addictive, like a dream you don’t want to wake from.

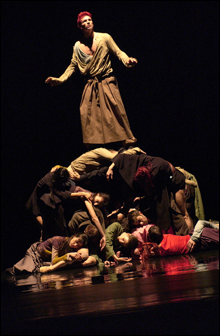

Loin was equally mesmerizing. The long, straight line that the dancers keep returning to hardly seems an interesting motif, but Cherkaoui more than compensates by having the dancers intone or mime hilarious tales involving the difficulties of touring (complete with the “monster” cockroaches who shared stages with them) or by moving the dancers through a polite ballroom dance of intertwining arms and foreheads resting against one another. The comedy of the stories does nothing to prepare one for the all-out dance phrases. The dancers are up, and then they’re down, with nary a sound. The sheer inventiveness of how they get there — now in quicksilver sweeps to the knee, now through the back by way of a shoulder — feels like a quick lesson in dance evolution, from folk dance to hip-hop. Whereas in Para-Dice the dancers are carried by air currents, in Loin, the unceasing sweep is of the tides.

The following week, the Mark Morris Dance Group arrived for its week at the Pillow, bringing three newish dances (two that premiered this year and one from 2005) as well as Love Song Waltzes, which premiered in 1989, when MMDG was still the house company at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels. The new pieces do not show well alongside the Brahms cycle; whereas the parts of the Genevans’ dances flow into a whole, Italian Concerto, Looky, and Candleflowerdance feel like so many disparate phrases that do not jell.

Morris is invariably lauded for his musicality — but, this side of Merce Cunningham, isn’t musicality one of the first tenets of choreography? And for me, his “music visualization” as some call it, can be cloyingly pedantic. A man next to me replied to his grumbling companion, “Yes, it was boring, but did you see how the movements matched the music?” Do we really need the follow-the-bouncing-ball school of choreography? Morris has put in 25 years as the sole creator for his company, and he’s created many masterpieces in that time — but it’s hard to swallow a program of which three-quarters straddles the foul line.

At least there was live music, performed by Tanglewood Music Center Fellows. In the Andante of Italian Concerto, pianist Yauheniya Yesmanovich surrounded dancer John Heginbotham with a breathtaking hush that helped make this solo a poignant snapshot of one man’s vulnerability and loneliness. And Stravinsky’s Serenade in A — the music for Candleflowerdance — was played with stark simplicity by Yegor Shevtsov. This dance takes place largely within a taped-off square in the center of the stage, a shape that evokes now a gymnast’s mat, with the dancers taking care to stay within the boundaries, and now a boxing ring, with the dancers pushing off one another in preparation for a match. Only toward the end — when the six dancers line up in various formations of the square, then lean, skitter toward a corner, and collapse softly together — does Candleflowerdance feel like more than just a jumble. This is where it should begin; instead, it’s over.