BEAT: No other American poet sounds like Whalen, though Ginsberg and Kerouac come close. |

| The Collected Poems of Philip Whalen | Edited by Michael Rothenberg | Wesleyan | 920 pages | $49.95 |

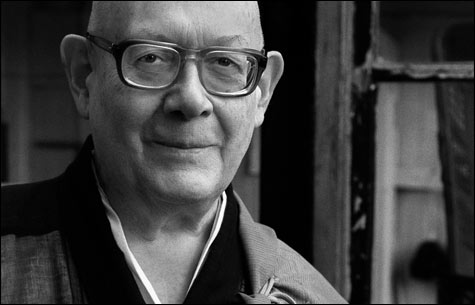

Philip Whalen (1923–2002) is a great American poet. Some — too few — readers have known this since the mid 1950s, when his poems first appeared in little magazines and small-press books. In publishing The Collected Poems of Philip Whalen (edited by Michael Rothenberg), Wesleyan gives the world at large this incomparable poet, and a major literary event. The book is huge (920 pages!) and at $49.95 expensive. Readers may have to forgo a few lunches or just slap their plastic down with blithe abandon. Either way, you will enjoy Whalen’s poems, and you may come to love them.This is Whalen in high gear, from “Hymnus Ad Patrem Sinensis”:

I praise those ancient Chinamen

Who left me a few words,

Usually a pointless joke or a silly question

A line of poetry drunkenly scrawled on the margin of a quick

splashed picture — bug, leaf,

caricature of Teacher

on paper held together now by little more than ink

& their own strength brushed momentarily over it.

Their world & several others since

Gone to hell in a handbasket, they knew it —

Cheered as it whizzed by —

& conked out among the busted spring rain cherryblossom winejars

Happy to have saved us all.

31:viii:58

Whalen is kin to those ancient Chinamen, and his American cohort includes Gary Snyder (classmate at Oregon’s Reed College), Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Joanne Kyger, Michael McClure, Charles Olson, and, perhaps the most significant influence on his writing, Jack Kerouac. Whalen was a Beat writer who read at the famous Six Gallery event at which Ginsberg debuted “Howl.” He adored Jane Austen and Gertrude Stein, had more than a passing knowledge of several realms of science, read widely in ancient and modern history, and was a thoroughly cultivated gent, “a Fat and Silly poet” who rarely took himself seriously. He committed the last 35 years of his life to Zen Buddhism.

In a note that appeared in Donald Allen’s groundbreaking anthology The New American Poetry, Whalen wrote, “This poetry is a picture or graph of the mind moving, which is a world body being here and now which is a history. . . . ” Since Whalen dated most of his poems in the same form he dated “Hymnus,” his Collected can be read like a diary or scroll. His book is not a story, though themes do emerge. He called his poetry a “nerve movie” — which is more accurate than most poets get about their own work. The other way to read his Collected is to start anywhere and let the momentum carry you in whatever direction you like. If you have a particular interest in Kyoto, go to page 502 and read the poems he wrote during his year in that city.

The distinguishing features of Whalen’s poetry are its playful freedom (he will leap, jolt, erupt into inspired nonsense like “Clara Barton Batten Durstine & Osborn/incunabula tightrope novel of blank mind”), its whizzing momentum, its offhand erudition, its quick eye, its radar ear. But what stands out is his voice. No other American poet sounds like Whalen, though Ginsberg in his less vatic moments and Kerouac in his novels come close. By voice I mean that quality akin to personality, instantly recognizable and open to mimicry, a power that creates appealing word bombs that continue to set off lengthening chains of associations long after you close the book. “Walk away from the page,” Whalen writes in “Minuscule Threnody, “That poem never ended.”