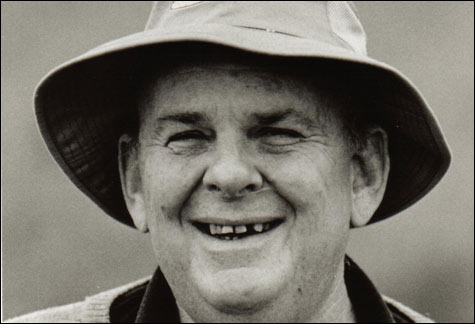

GNOMIC: Murray flits between styles with a fat man’s supernatural grace |

The Biplane Houses | by Les Murray | Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 110 pages | $23 Collected Poems for Children | by Ted Hughes | Farrar, Straus and Giroux | 272 pages | $18 |

Les Murray and Ted Hughes, though they dwelled in each other’s antipodes, had plenty in common. Their names, for a start: sawn-off, thick-handled workingmen’s names that bespoke the ruggedness of their origins — Murray’s in a tin shack in New South Wales, Australia, Hughes’s in the unlettered valleys of West Yorkshire, England. Both were country boys, born eight years apart, who by dint of natural force and brilliance, and a faith in poetry that seemed at odds with the age, projected themselves out of the margins and into the center of national/spiritual life. In 1984 Hughes, famous already, was appointed Poet Laureate of England. In 1999, when Prime Minister John Howard announced that a new Preamble to the Australian Constitution was being drafted, he told journalists that he had enlisted the help of “the best writer in the country.” “Who’s that?” they asked. “Les, of course.” Hughes died in 1998, at the grizzled peak of his renown. Murray is still with us, huge, bald, and revered, the heavyweight of Australian poetry.

The names of Hughes and Murray have both been polarizing — the former because of a feminist death cult that attached itself to his wife Sylvia Plath in the wake of her suicide in 1963, the latter because of his ribald distaste for Modernism, political correctness, and what he calls “the Generation of ’68.” (There is some overlap here: after Hughes’s death, Murray wrote sympathetically of the Englishman’s “long torment at the hands of militants,” which he had seen for himself in 1976 when Hughes showed up to give a reading at the Adelaide Festival and was met by a mob chanting, “You murdered Sylvia!”) And without wanting to give a hostage to psychoanalysis, it must also be pointed out that behind each of these poets was the gloom of a silent father. Billie Hughes, father of Ted, never talked about what he had lived through as a soldier at Gallipoli and then Ypres: “My father sat in his chair,” wrote Hughes in his poem “Out,” “recovering/From the four-year mastication by gunfire and mud. . . . ” Cecil Murray, father of Les, was rendered near-catatonic by the death of his wife; that left his 12 year-old son to run the dairy farm by himself. “Getting near dark, I’ll go home, light the lamp/and eat my corned-beef supper, sitting there/at the head of the table. . . . ” (“The Widower in the Country”).