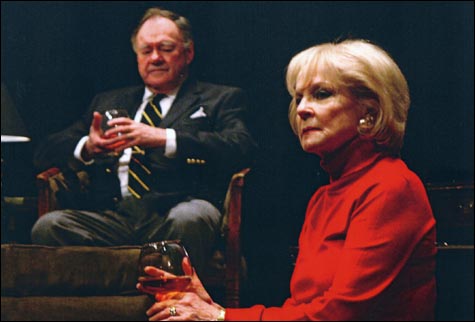

A DELICATE BALANCE: Can Penny Fuller tempt Jack Davidson into the garden shed in Albee’s underrated follow-up to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? |

A Delicate Balance is 40 years old now, but like the patrician clan at the frightened heart of it, the play has good bones. Edward Albee’s 1967 Pulitzer Prize winner, now getting a pitch-perfect revival from Merrimack Repertory Theatre (through April 6), was written on the cusp of the Summer of Love, in the wake of The Homecoming. Yet the old-fashioned three-act play starts off like upper-class drawing-room comedy, with wealthy Agnes and Tobias enjoying an after-dinner libation in their well-appointed parlor. Except that the subject of Agnes’s genteel chatter is the possibility that she might someday lose her mind, Somerset Maugham might be lurking. Even Agnes’s alcoholic sister Claire, blowing the dust off old hurts and rivalries, can’t quite spoil the cocktail party, over which Tobias presides like a country potentate. Neither can the likelihood that daughter Julia will soon be on their doorstep, fleeing a fourth failed marriage to batter at the bosom of her family, ruffle the suburban composure. But existential terror is about to start leaking into the air-conditioning, as long-time best friends and country-club cronies Harry and Edna show up unannounced. It seems they were having a quiet evening at home when they were overcome by a vague terror. “We couldn’t stay there, and so we came here,” Harry explains blandly. Will the hosts allow these “plague”-trailing intruders to poison their false comfort zone?

Despite winning the Pulitzer that Albee had been denied four years earlier for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, A Delicate Balance has always seemed a David next to that Goliath of an allegorical marital meltdown, with its rough chemical peel of illusion. It’s only since its successful 1996 Broadway revival that the later and subtler work has started to glean the attention it deserves. A year ago, Trinity Repertory Company produced a well-acted revival that was nonetheless not so expertly cast and calibrated as this one, whose characters seem to have stepped right out of period and into The Twilight Zone. Even Penny Fuller’s bad-girl Claire, plinking devastating one-liners into her “willful” cups, is a bad girl of an era: an aging Sandra Dee, still trying to tempt Tobias or Harry into the garden shed for a reprise of their own sad, triangular, long-ago summer of love in the wake of devastating loss skimmed over and now part of the conversational wallpaper.

Despite being elegantly written, A Delicate Balance could as easily lurch in the direction of farce as toward poignancy and disturbance. Director Charles Towers brings all the roads together, so that even the over-the-top scene in which Julia — arrived home to find her passive-aggressive godparents invaders of what she had considered a private retreat — physically defends the cocktail cabinet is both hilarious and horrifying, so coltishly crazed is Gloria Biegler’s woman child betrayed. As Harry and Edna, Ross Bickell and Jill Tanner, the former stodgily bespectacled, the latter sporting a hairdo that is almost an auburn helmet, tiptoe across the line from dully harmless to menacing.

But the heart of this stellar production is made up of Jennifer Harmon’s prim martinet of an Agnes and Jack Davidson’s shlubby diplomat of a Tobias, the latter a familial board chairman trying to buoy up the illusion of righteous, loyal bonhomie that has sustained his arid, affluent life. Albee has written a rising, piquant hysteria into the scene in which Tobias, eager to establish his goodness, tries to persuade the intruding friend he wants gone to stay. And Davidson not only faces the manly music, he makes a desperate, dictatorial symphony of it.

The last thing Company One resident playwright Kirsten Greenidge is attempting in The Gibson Girl (at the BCA Plaza through April 5) is a well-made play. She takes her themes — which have to do with culturally dictated female image and the need to create an African-American family — and tosses them all over the place, hoping they will somehow cohere as she pulls the pieces of her scattershot puzzle together. She wants to be Suzan-Lori Parks, but she lacks Parks’s originality and consistency of vision. Indeed, several scenes of the play are set in a private-school bathroom where the less conventional of a set of adolescent twins hangs out, plastering the walls with images of her inspirations, from Malcolm X to Toni Morrison. Parks is there, hovering above the toilet into which Greenidge threatens to take her.

Twins Valerie and Win — one light-skinned, the other dark — are the ostensible progeny of Ruth, who has resorted to desperate means to lure her abandoning husband back. She has consulted a Jamaican psychic, who seems to see through her and has attached faucets to her maple trees, hoping the sap will be a siren call to the rhetoric-spouting PhD who took their light-skinned daughter as a sign from God to vamoose toward a philosophic destiny somehow tied to advocacy of the racially pure black woman, a Nubian queen pointing the way toward a “glistening future.” It appears this paragon liked syrup, but given that the man has taken a post at a college in Vermont, isn’t sending whiffs of maple fragrance his way like batting coals in the direction of Newcastle?