WHAT IS TIME? WHAT IS DEATH?: The two LOA volumes compose an unresolved fugue of philosophical and psychological obsessions. |

| Philip K. Dick: Five Novels of the 1960s & 70s | Edited by Jonathan Lethem | Library of America | 1148 pages | $40 |

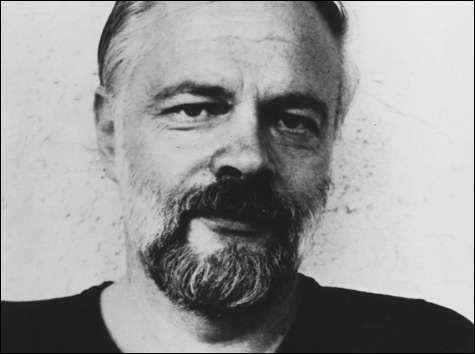

The Philip K. Dick phenomenon might be petering out. At least if movie adaptations are any indication. They seem to flourish when the GOP is in power: Blade Runner during the Reagan administration in 1982, Total Recall under the elder Bush in 1990, Minority Report and A Scanner Darkly during the reign of George W.Published last spring, the first Philip K. Dick volume in the Library of America series caught this wave at its peak. This new offering might not be so fortunate. Could renewed optimism and faith in the political system have dispelled the cynicism and the paranoia that draw readers to Dick? Never fear: the next terrorist attack, needless war, shocking assassination, economic collapse, or Republican administration will put the Dick industry back in business

In the meantime, Philip K. Dick: Five Novels of the 1960s & 70s, edited by Jonathan Lethem, who did the first volume, can be read in a more personal context. Taken together, the nine novels in these two collections compose an unresolved fugue of philosophical and psychological obsessions, mapping twists and turns in an exhilarating and terrifying mental labyrinth.

Rather than being simply an exercise about imperialism in an extraterrestrial setting, Dick’s 1964 novel Martian Time-Slip poses the kind of questions that might bug a brilliant mind cranked up on speed at three in the morning. Like, what is time? That proves a headscratcher on the sparsely settled Red Planet colony where Goodmember Arnie Kott, the crudely ambitious but nonetheless appealing head of the powerful Water Workers Local plumbing union, figures that what he needs to get ahead is a “precog,” someone with the gift of prophecy. For though the planet’s climate might not nurture much in the way of agriculture, it has spawned a generation of autistic children, and according to Dr. Glaub, a Martian psychiatrist, these enfants terribles suffer from an inability to experience time sequentially. Like God, they see everything happening at once in a single everlasting instance.

Such unfortunates, Kott figures, must be able to see the future, so they could tip him off on good real-estate investments before other speculators catch on. He engages Manfred, one such afflicted child, for his purposes. What he fails to take into consideration is that Manfred sees everything at once “under the aspect of eternity” — that is, in the context of its ultimate destiny: death and nothingness. And not only can he see what lies ahead, he can control it, drawing the consciousness of others into his own dismal perception of a “tomb world” inhabited by “gubbish,” debris that once was alive and beautiful.