THE CHERRY ORCHARD: The Nora does Chekhov’s final masterpiece with sincerity, respect, and, occasionally, daring. |

T.S. Eliot famously opined that John Webster saw "the skull beneath the skin." In David R. Gammons's staging of the Jacobean dramatist's The Duchess of Malfi for Actors' Shakespeare Project (at Midway Studios through February 1), we see the skull beneath the stage. In the director's scenic design, the 1614 revenge tragedy is played out on a long runway overhung by crystal chandeliers and bookended by gilt-edged doors. But beneath the narrow strip of a playing space are strewn caches of bleached bones: skeletons in the basement — perhaps because, in a milieu so murderous and corrupt, the closets are full.

Actors' Shakespeare Project, veering from the canon for the first time in its five years, bills this Duchess of Malfi as the first professional staging in Boston. Certainly it is the first in elephant memory. American Repertory Theatre plunged into the perverse and lethal doings of Thomas Middleton's The Changeling and John Ford's 'Tis Pity She's a Whore. But this is the first time I have witnessed Webster's dark, poetical swirl of covert passion and outsized revenge, one peopled by flatterers, panders, "intelligencers," and worse. In the midst of the Jacobean fray is the title character, a rich, aristocratic young widow who lusts for and secretly marries her steward, inciting her two nasty brothers — "like plum-trees that grow crooked over standing-pools" — to a take-no-prisoners revenge that encompasses strangulation, psychic torture, fake severed limbs, and a poisoned Bible. One of these powerful if unsavory sibs is a kinky cardinal with a married mistress, the other an incestuously unhinged duke, Ferdinand, who does time toward the end as a werewolf!

With all that Jerry Springer material at hand, it's a wonder that Gammons, trimming the script and conflating its secondary characters into a two-man ensemble that serves as officers, servants, madmen, and hit men, is able to pull focus to the conflicted character of Daniel de Bosola, a former soldier and galley slave who becomes the brothers' spy but lives (if briefly) to regret it. Not that his repentance isn't portended in the self-loathing that accompanies his assault on advancement. Helped by Ferdinand, the volatile duke with an unhealthy yen for his twin sister, to the position of "provisorship o' the horse" in the duchess's household, Bosola sneers that "my corruption/Grew out of horse dung" and proceeds to stink up the place, discovering first the duchess's pregnancy and then the identity of her partner and reporting all to the cool, corrupt cardinal and the unstable duke. Bill Barclay is an engaging, sometimes incredulous Bosola, though lacking the rough edges of the character's former employments.

As with his plasma-free Titus Andronicus for ASP, Gammons's staging is stylized. At the center of the runway sits a plexiglass chair occupied at the beginning by Jennie Israel's duchess, a smug earth mother in a Marie Antoinette wig, seductively flexing the fingers that extend from a gauzy black glove. Next to her brothers, this defiant duchess is, for all her appetites (including a tell-tale one for "apricocks"), a paragon. And at ASP, her palace a prison where the comings and goings are propelled by jangling music and the repeated clanging of slamming doors, she dies a stoic, almost triumphant death — far nobler than those of the less savory characters who follow her like dominoes in a work that could as easily have been inspired by an Elizabethan tavern dare to one-up the death count of Hamlet as by a jaundiced world view.

This is not a perfect production. In Gammons's uncluttered, mostly sinister staging, the singing, dancing loonies engaged by Ferdinand to drive his sister to distraction seem to have broken out of an asylum on Sesame Street. But the performances are credible, with Jason Bowen a four-square Antonio Bologna, the anti-Malvolio who wins the duchess's heart, Michael Forden Walker a sulking, animalistic Ferdinand, Joel Colodner a very creepy cardinal in fishnet stockings, and Marya Lowry fierce in two roles.

Ah, but the play — presented rarely enough that theater aficionados will want to see it, whatever its failings. The Duchess, especially in its second half, hurtles toward a ludicrous excess that's impossible to play down, however ritualistic the staging. True, the work bespeaks a bleak modern sensibility: compare Bosola's "We are merely the stars' tennis balls" to Gloucester's "As flies to wanton boys are we to th' gods." But though written at the tail end of Shakespeare's career, it shows Webster more a contemporary of the Titus scribbler than of the man who wrote King Lear.

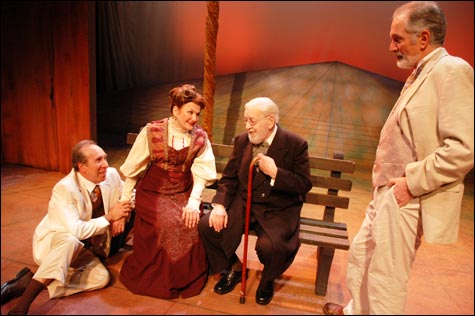

A gentler, more familiar landscape is The Cherry Orchard (at Central Square Theater through February 1). No new interpretive trees are planted in the Nora Theatre Company's solidly acted production of Anton Chekhov's final masterpiece, which is heard here in a colloquial new version by Russian speaker George Malko, whose previous translations include Chekhov's complete short plays. The rhythms — with their alternation of political or poignant speechifying with non sequitur — are recognizably Chekhovian. Director Daniel Gidron whips the requisite element of farce into the pathos. And a cadre of Boston actors, tucked into Arthur Oliver's period costumes, pull off the playwright's near-symphonic 1904 ode to expulsion from a questionable Eden with sincerity, respect, and, occasionally, daring.