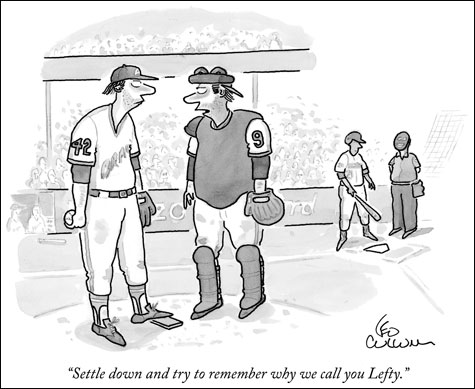

© The New Yorker Collection 2005 Leo Cullum from cartoonbank.com. All Rights Reserved.

The first pitcher/catcher cartoon in the New Yorker was also the simplest. Drawn by Garrett Price, in the June 14, 1941, issue, it depicts a catcher, decked out in the tools of ignorance, face mask still on, approaching his pitcher for a powwow.

His advice: “Strike him out.”

“I’ve always loved that one,” says New Yorker (and, we should note, Boston Phoenix) cartoonist David Sipress. “When the manager or the catcher go out to the mound to talk to the pitcher, everyone in the world, on some level, is thinking, ‘What the fuck? What in the world could possibly be useful or relevant in what he’s saying?’ ”

This past June, Sipress drew another one-panel for the New Yorker on the same subject. Standing on a sandy mound in the middle of Shea Stadium, a right-hander complains to his backstop: “I know I could keep my slider down if they would just fire the manager.” (For those not up on the minutiae of New York baseball, that’s a sly commentary on the travails this summer of since-canned Mets skipper Willie Randolph.)

Between Price and Sipress’s cartoons, there have been at least 20 other visits to the pitching rubber in the pages of the New Yorker over the years.

In April 2001, Michael Crawford made light of Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez’s remarkably acrobatic wind-up. “Gimme a hand,” the Yankees righty, his cleat lodged inside his elbow, said to his approaching battery mate. “I’m stuck.”

In October 2006, Leo Cullum imagined a catcher’s novel remedy for a bases-loaded jam: “Let’s go slider, fastball, curve, beanball, fight, ejection, shower, beer.”

This past June, Danny Shanahan sketched a pitcher peering plateward, a pigskin in hand, about to go deep. “There’s your problem,” the catcher opined.

Cartoonists often indulge in certain visual tropes, over and over again, notes Sipress. The Grim Reaper. Aliens. Cats and dogs. Snowmen. The Pearly Gates. Medieval prisoners hanging from shackles in dungeons. The wild-eyed street prophet wearing a sandwich board.

The pitcher-catcher conversation is just another example of that grand tradition. In fact, Sipress sees the pitching mound as analogous to another classic set piece. “The mound is a little like a desert island, in that there are these two people in an isolated place.”

I suggest that two people talking in private, each counting on the other in an intimate codependent relationship, suggests another cartoon cliché: the husband and wife in bed. Sipress agrees, adding that “it’s like two people in bed in the middle of a stadium. The absurdity of them having a private conversation in the most public arena is ultimately what’s so funny.”

Invite the Ump

Reached in Manhattan, New Yorker cartoon editor Robert Mankoff says the magazine’s fabled fact-checking doesn’t stop at the margins of the text layout. Cartoons get scrutinized, too.

In Sipress’s Mets cartoon, for instance, the pitch was initially called a curveball — “but we determined that it’s the slider you wanna keep down,” says Mankoff, “so it got changed.”

But far beyond any factual accuracy, of course, a cartoon must be funny. And that’s why cartoonists so often walk that fine inky line between the familiar and the cliché.

“We have lots of cartoons on lots of topics,” says Mankoff, who sees 500 or 600 cartoons a week. The key is how the image is treated. “One of the reasons you have something that’s instantly recognizable,” he adds, “is so it’s instantly recognizable.” The humor comes when you take that “default script and [it’s] violated for a joke.”

The pitcher with the football in his hand is pure sight gag. Sipress’s Willie Randolph commentary pokes fun at the absurdity of a real-life situation. (As does Jack Ziegler’s cartoon in which a catcher approaches the mound to inform his teammate, “Mr. Steinbrenner wants you to stop spitting during the close-ups.”)

“On one end are things that are just silly and we like them because they’re silly,” says Mankoff. “On the other are things that are funny and incongruous, but somehow the joke makes sense.”

Mankoff starts thinking out loud — and offering potentially valuable insights one might use to win the New Yorker’s popular caption contest. Why not invite the ump to the party?

“I don’t really have a line yet, but I would,” he says. “The umpire might come out and say, ‘Want my opinion?’ ”

Or, he suggests, the catcher might use some highfalutin’ policy jargon, like, “ ‘Stick with your fastball, your curveball’s lost its credibility.’ In other words, you use language. You just imagine them talking about something completely unrelated. Like real-estate values. Or political endorsements.”

In the comedy world, Mankoff reminds us, “everything that’s bad is good.” It’s the mishaps and the bum luck that make for the funny moments. And, of course, this is a bad situation: the catcher is helping the pitcher cope with a problem. “But it’s not that bad.”

In fact, some catchers are known to tell a joke or two to help clear their pitchers’ heads and put things in perspective.