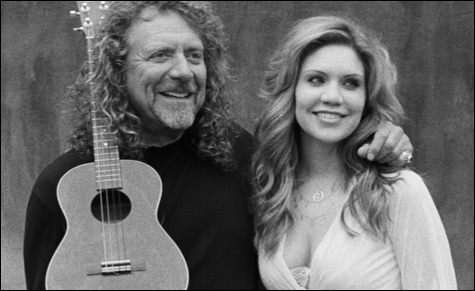

TIMELESS: On Raising Sand, Krauss and Plant serve up 1920s blues and pop, traditional country, and rickety old rock and roll. |

There’s a blues and old-school R&B resurgence rumbling in the indie-music underground, and it goes well beyond the icky thump of the White Stripes. Its first populist signs are fresh albums featuring Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant collaborating with bluegrass diva Alison Krauss and soul survivor Bettye LaVette teaming with Dirty Southern rockers the Drive-By Truckers.This creative movement began percolating in the mid ’90s, when the Fat Possum label released the nastiest, punkiest authentic juke-joint blues in decades. Through shrewd marketing, hip-hop remixes, and the support of rockers like Iggy Pop and Jon Spencer, old Mississippi dogs like R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough found a new audience of young pups. Those pups — including Jack White — began digging back to ’60s icons like Fred McDowell and to acoustic Delta kingpins Son House and Robert Johnson, whose songs have since been covered by, among others, the White Stripes (House’s “John the Revelator” and “Death Letter”) and Juliana Hatfield (Johnson’s “Malted Milk”).

In 2000, bluegrass got a big bump thanks to the smash soundtrack for Ethan and Joel Coen’s O Brother, Where Art Thou? The resulting rediscovery of mountain musicians like Ralph Stanley, Doc Boggs, and Bill Monroe triggered a bluegrass and old-time-music renaissance, with more new bands than you can shake a mandolin at. Charlottesville’s King Wilkie and Boston’s Tarbox Ramblers are among the established exponents. This year, younger outfits like Portland’s Blitzen Trapper and Seattle’s Cave Singer have stepped to the fore.

Now, it seems that blues and R&B are getting their turn. An eruption of new bands, labels, festivals, and musical surprises like Plant & Krauss’s Raising Sand (Rounder) and LaVette’s The Scene of the Crime is generating cultural heat.

The White Stripes, North Mississippi All Stars, and the Black Keys have been the grungy point men. But a generation of newer bands also informed by the roughshod sounds of the South — much the way the Allman Brothers had been — is staking its claim. Nashville’s Black Diamond Heavies and the Dynamites, Kansas’s Moreland & Arbuckle, Memphis’s Richard Johnston, Oregon’s Hillstomp, and Texas’s Jawbone are among the sharpest new knives in a cutting-edge strain of dirty blues and R&B spiked with rock-and-roll energy. Most of them convened back on August 18, in River Falls, Wisconsin, for the Deep Blues Festival. It was billed as the first punk-blues fest, and its small-but-rabid audience came from throughout the US and abroad. Last year, however, a bunch of Mississippi musicians got the drop on the Midwesterners by debuting the North Mississippi Hill Country picnic in Potts Camp. That bill was mostly traditional, but this June the two-day event brought in the All Stars, Austin’s Goshen, Cary Hudson of Blue Mountain, and the funky rock polyglot Taylor Grocery Band, featuring Kimbrough’s drummer son Kinny. Both festivals will reconvene in 2008.

Although this is a cautious time for the CD biz, a few hip labels have dived into the new-dirty-blues fray. Yellow Dog is doing its part with a hybrid R&B of the Soul of John Black (whose latest album was helmed by legendary Hi Records producer Willie Mitchell), the string band Asylum Street Spankers, and powerhouse soul groovers the Bo-Keys. But the riskiest route belongs to King Mojo Records of Smyrna, Georgia, which delivers nasty modernist blues from Big Shanty and Little G. Weevil along with good ol’ Allmans-style Southern rock.

Most surprising is the resurgence of Stax. The Memphis label was ground zero for unadulterated soul and blues in the 1960s and early ’70s, and a force in the civil-rights movement. Thanks to financing from Concord Records, a flood of classic Stax recordings and previously unavailable filmed concerts is seeing the light of day. The label plans to release its first new discs since 1972, by Stax vets Isaac Hayes and Eddie Floyd and newcomer Angie Stone. Floyd’s album was cut in Boston by producers Michael Dinallo and Ducky Carlisle.

The next 12-month business cycle of the music industry should determine the impact of this emergence of vital contemporary music with weathered roots. From LaVette’s perspective, something has taken hold — at least for her. After 40 years in obscurity, the powerhouse R&B singer’s 2005 I’ve Got My Own Hell To Raise (Anti-) earned her an ardent following that cuts across age and racial demographics.

“It’s extremely flattering to have a brand new audience,” says the 59-year-old. “They’re young, but I tell them they have to behave as if they were at their grandmother’s house, because I expect their attention.” She earns it with honey-and-grits singing and dramatic performances.

“I don’t take them for granted, because people can be fickle,” LaVette adds. Right now, she’s in the clear. For At the Scene of the Crime, the Truckers sublimated their garage instincts to create the best Muscle Shoals soul album in more than 30 years.

Meanwhile, Raising Sand has all the hallmarks of an artistic watershed. Plant has delved into world music and blues ever since Led Zeppelin’s inception in 1968. Krauss, who contributed to the O Brother soundtrack, is already a country and pop-crossover success.

On Raising Sand, they put their well-established musical identities at the service of a sonic universe of 1920s blues and pop, traditional country, and the breed of rickety rock and roll that Tom Waits favors. Plant croons with tranquility and grace and rarely sounds like his usual muscular self. Krauss’s breathy delivery works as a wonderful foil. Most important, Raising Sand makes old American music sound new. And, more and more, it seems that old American music is the new paradigm.