CRAZY! Les 7 Doigts de la Main combine choreographed acrobatics and dance — in character. |

Montreal breeds a seemingly infinite number of new-circus companies. It's the home of the Canadian National Circus School, after all, and the sprawling entertainment factory Cirque du Soleil. We've seen new-circus shows featuring everything from dancing horses to buffoonery. Founded in 2002, Les 7 Doigts de la Main ("The 7 Fingers") dispense with glamorous trappings to take a small-scale look at everyday life as infiltrated by circus skills.

In Psy, at the Cutler Majestic last weekend, neurotics imagine themselves in various states of levitation, distortion, and superphysicality. Each of Les 7 Doigts' 11 artists plays, at different times during the evening, both a mental patient and a psychiatrist. As the patients start telling their stories to their shrinks, the stage blossoms into splendid fantasies. Gloom and apprehension explode into mass-engineered chaos and survival. None of the afflicted gets cured in the course of the evening, but somehow what they can do in their dreams provides some respite and deflects their fears.

Toward the end of the first act, the performers stand in a semi-circle and announce their name and their problem, to begin a group-therapy session. By that time, we've seen Michel Michel (Guillaume Giron), who hears voices, dangling by his fingers on a fixed trapeze. And John? Joe? Jim? — the amnesiac (Florent Lestage) juggling three Indian clubs and a cane while walking backwards and doing flips during his tenth-birthday party. And Suzi (Olga Kosova), who suffers from intermittent-explosive disorder, gleefully relieving a fit of rage by twirling a couple of nasty-looking cleavers.

Most of the individual stories eventually open up to include the whole company, a crew of experts at tumbling and airborne acrobatics, hand-to-hand balancing feats, and juggling. They're also dancers — the whole show is choreographed so that the circus moves are woven together with dance moves — and they can act their characters with casual comic assurance.

Each performer's specialty emerges from his or her disturbed character. Johnny the addict (Julien Silliau) revolves dizzyingly inside a German wheel, a double-rimmed circle about six feet in diameter, that he climbs inside and propels on edge, his body splayed out or gyrating in the center. Jacques the hypochondriac (Olaf Triebel), finding himself in a café where all the patrons shun him as if he were contagious, does handstands on four tiny pedestals, twisting his body into pretzel shapes.

Lily the agoraphobic (Danica Gagnon-Plamondon) is goaded by her helpful therapy group to try swinging on a trapeze. Cheered on, she pumps higher and higher, and when it gets going, she hurls herself ecstatically around and off it in no-handed air turns and breakneck rotations.

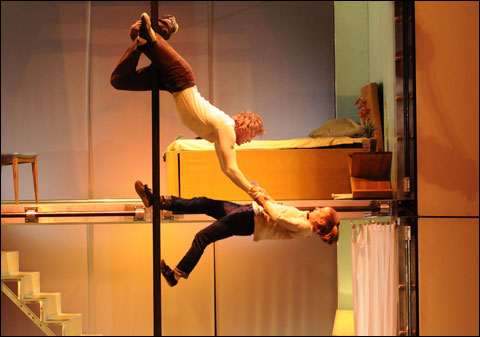

My favorite case was Lily the narcoleptic (Héloise Bourgeois), with her sympathetic partner George the paranoiac (William Underwood). When he comes home from work — the set for the show is a multi-purpose two-story structure that turns into a house when needed — she can barely greet him before she collapses into sleep. With exquisite timing, Bourgeois can go limp in an instant. This is funny when she falls onto the bed, absurd when she topples off the edge of the cutaway second-floor room clutching her pillow and slides down a convenient pole. She and Underwood then have an extended duet on the pole. She droops and grabs on, he hangs just behind her, ready to wrap his arm around her as she lets go, or make a split-second save inches from the floor.