YES! The Jones/Zane partnership came to life in a new generation of dancers. |

Arnie Zane died of AIDS in 1988, but the bond he shared with his partner, Bill T. Jones, remains in their company's name. It also remains in Zane's reputation as a dancer, choreographer, photographer, and goad to Jones's talent and ambition. Three decades of work later, Jones's controversial dance theater has earned him MacArthur, Tony, and Kennedy Center awards and made him as close to a household name as any choreographer alive.

Body Against Body, the much-anticipated retrospective of three Jones/Zane works created between 1977 and 1980, arrived for its world premiere at the ICA burdened with nagging questions. Were Zane's performance works significant beyond their historical interest? Could younger dancers replenish the choreography? And, not at all least, would Zane's 30-years-plus postmodernism hold up?

Not to get too Molly Bloom about it, but yes, yes, and yes.

Jones and Zane were a pepper-and-salt, Mutt-and-Jeff pairing. Critic Jim D'Anna observed in 1983, "When Jones dances he seems to be carving out space. When Zane dances he seems to be measuring it." Compared with the men seen dancing Monkey Run Road in grainy black-and-white archival footage, Erick Montes (in the Zane role) is silkier, whereas Talli Jackson (in Jones's) is more inclined to foreground the work's athleticism.

Monkey Run Road opens with the two men chatting and rolling a big wooden box on casters onto the stage, as if making a delivery from a freight elevator. Zane's stringent photographer's eye comes through in the way the dancers' shapes, perched on the edge of the box, diving headlong in, are framed by empty space.

Monkey Run Road runs ruts into your brain with its repeated patterns, so you breathe in anticipation of a phrase. Then the choreography subverts that expectation by displacing the motion just a tad. Jackson's tender palm on the back of Montes's neck is suddenly displaced into the air, flipping upward as if to catch a handful of rain. The men dance as fulcrum and lever, as Jones's recorded voice reminisces about the Bay of Pigs crisis, when he was sure that the end of the world was near.

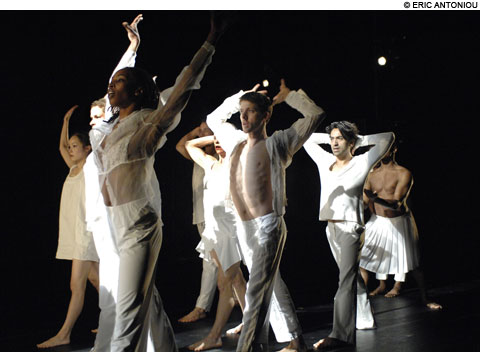

In 1991, Jones reimagined and restaged Zane's 1977 Hand Dance as an ensemble work, Continuous Replay. It's a dance of nakedness, a postmodern accumulation strategy crossed with a reverse striptease. The frieze the dancers make resembles a herd of centaurs with heavy haunches and curving necks scissoring their arms with an audible hiss. Oddly enough, these nude figures seem more individuated and freer to resist conformity once they've added some clothes.

Blauvelt Mountain, the 1980 companion to Monkey Run Road, combines set choreography with verbal free association. Apparently unchanged, the duet is now danced by a mixed-gender couple. Jennifer Nugent takes on Zane's barrel turns and saucy Donald O'Connor skips. Paul Matteson, an authoritative dancer with actorly legibility, drives an invisible roadster from his perch on a stool. The performers' alert word game makes for humorous juxtapositions; among the words thrown out on Friday were "mascara," "conjunctivitis," and "reindeer."

In his autobiography, Last Night on Earth, Jones writes, "Arnie and I formed some mythical beast. We flew. I had the wings, but it was something about the strength in his legs that got us off the ground." Both Monkey Run Road and Blauvelt Mountain end with one dancer leaping into the other's arms, lifted high into the air, flying. "Still/Here" indeed.