BLUE HEAVEN Larkin could never quite rid his poetry of an Eden-like clarity of perception, attack it as he might with pornography and amber fluids. |

"A smash of glass and a rumble of boots/Electric trains and a ripped-up phonebooth/Paint-spattered walls and the cry of a tomcat/Lights going out, and a kick in the balls." These lines are not by Philip Larkin, of course — they're by Paul Weller. And though nothing would have induced Larkin to listen to the Jam's "That's Entertainment" (he famously deplored every development in popular music post-Sidney Bechet), could he somehow have been made aware of the lyrics. . . well, the old fucker might have been obscurely gratified. Here, after all, coming to pop fruition, was an impulse that he himself had injected into English poetry. Here, itemized in the sawn-off imagery of his later verse, was terminal England: yob-besieged, not working well, destitute of spirit. The tomcat's cry is bit naff, perhaps — but the author of "This Be the Verse" ("They fuck you up, your mum and dad") and "Here" ("Cheap suits, red kitchen-ware, sharp shoes, iced lollies. . . .") would have loved Weller's last, emphatic toecap to the gonads. "A Grecian statue kicked in the privates," he wrote in "If, My Darling," describing the contents of his own head.

Larkin's punk-rock side — his taunting, scatological, spank-mag side — has still to be accommodated, really. He died in 1985, a year after declining the post of Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, with his reputation apparently secure. To the reading public, he was the poet of "Church Going" and "Cut Grass": lyrically gloomy, a pained quietist, death-obsessed, sure, something of an atheist, but a wistful, doleful, respectable atheist. An Englishman, damn it — less an atheist than a disappointed Anglican. "Hatless, I take off/My cycle clips in awkward reverence. . . ." and so on.

Then, with the publication of a selection of his letters in 1988, we met Nasty Larkin, for whom we were unready: the poet and critic Tom Paulin held his left-wing nose at this freshly revealed "sewer under the national monument," calling the book "a distressing and in many ways revolting compilation." Larkin's correspondence with his lifelong friend Kingsley Amis, in particular, was ripe for deconstruction. Rude about everybody (other genders, other races), the two men additionally abetted each other in a kind of wanker's nihilism, snarling and boozing and flicking V's at God. Most of this was already in the poetry, but somehow it came as news. Andrew Motion's 1993 Larkin biography, in which his subject's unsatisfactory love life, ignoble pleasures, etc., were thoroughly detailed, helped fill out — or further contract, maybe — the picture.

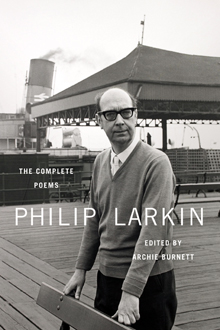

Editor Archie Burnett's new The Complete Poems, then, which backloads Larkin's slender output with a 300-page posterior baggage of notes and commentary, much of it excerpted from his own letters, is in a position to reconcile some contradictory ideas. The poet, the poems, the life: all at once, for once?