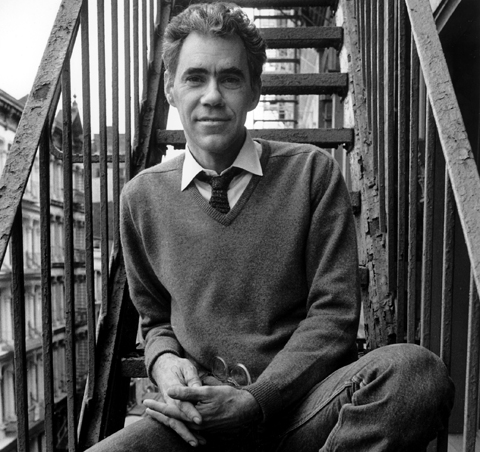

COLLECTIVE MEMOIRIST With I Remember, Joe Brainard created everyone's self-portrait. |

The sui generis artist and writer Joe Brainard invented a literary form. Not that he meant to when one summer afternoon in 1969, bored in his studio, he opened a notebook and with a felt-tip pen printed in his signature hand, "I remember."

"I remember the first time I got a letter that said 'After Five Days Return To' on the envelope, and I thought that after I had kept the letter for five days I was supposed to return it to the sender."

"I remember the kick I used to get going through my parents' drawers looking for rubbers. (Peacock.)"

"I remember when polio was the worst thing in the world."

"I remember pink dress shirts. And bola ties."

Soon Brainard filled many pages, and since he was practically the house artist — book covers, posters advertising readings, all manner of collaborations — for the New York School Poets of the first and second generations, he began to read from I Remember to delighted audiences. Publication soon followed.

Since we are what we remember, what emerged in Brainard's form is the self-portrait of a gay artist born in 1942 who grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a New Yorker before he set foot in the city. His readers discovered that, as they read, their own memories kicked in — Brainard had created everyone's self-portrait.

This appealed to poet-teachers who used "I remember" exercises as an icebreaker in their writing classes. The Collected Writings of Joe Brainard, edited by his lifelong friend, the poet Ron Padgett, with an introduction by Paul Auster, will bring Brainard a wider audience. Many will agree with Auster that, "I Remember is inexhaustible, one of those rare books that can never be used up."

There is much more in this big book than Brainard's masterpiece. There are journals and diaries — natural forms for him — poems, drawings with captions, essays, notes to himself, one-liners, mini-essays, and two interviews. All "minor forms," at least according to English departments and canon formations, about which Brainard cared not a fig. He aimed to please, and he delivered in ways that continue to surprise. His light touch mocks the heavy-breathing ambition of writers who believe they must have "something to say." Mockery was not Brainard's intention, but it is an inevitable aftertaste of writing that resists formulas declaring what writing ought to be.

"Writing, for me," he wrote," is a way of 'talking' the way I wish I could talk." Brainard had a slight stutter. He may be referring to this, but talking is the right way to describe his writing. It is artless, casual, comic, and witty, matter-of fact, youthful, and never glib or talky. When he read aloud, his modesty and obvious discomfort charmed his audience, and they laughed. Not at jokes, because his writing doesn't tell any, but at his observations delivered deadpan. This is the voice on every page he wrote.