That people only think of “Robert Downey, Jr.” when they think of Iron Man, this character with this rich and involved history.

Yeah! The beauty of the art form is something that’s just really neglected, despite all this attention that Marvel Comics has. Very little of it has to do with actual comics.

To me, that’s the conundrum: that, as much attention is put on Marvel nowadays, it isn’t actually helping them. Like in the ’80s, everyone was noticing comics. Comics were featured in articles in Time and Newsweek, in the wake of Watchmen and whatnot, think pieces like “Hmm, what’s up with comics growing up?”, that sort of thing. It was the Sgt. Pepper’s phenomenon of the ’60s, for the ’80s. Even in the ’60s, comics were taken seriously in a counter-cultural way, as you document in your book. But that doesn’t happen now: is that a failure of the industry, or is it a failure of the art form?

Well, it’s certainly not a failure of the people controlling the companies, because this is a profitable route for them. But you could do really well to hire someone like Dan Clowes to do Guardians of the Galaxy for a year, and consider it a loss leader, and then just watch as people who had written off superhero comic books start investigating it. Dan Clowes would never do a Marvel comic, but whatever — just as an example. When you aren’t just looking at the short-term bottom line, there are ways of building interest in comic books beyond this small closed circle that’s developed. But who am I to tell Marvel Comics, “You shouldn’t only have titles that are profitable”? But clearly, if you look at the history of Marvel it was when they took chances on things that they got long-term value out of it.

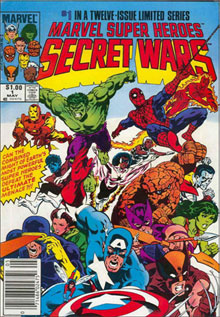

As a kid of the ’80s, I was a big fan of the series Secret Wars, which was a big tie-in series that was a huge blockbuster — mostly, as you laid out in your book, because of how calculated and pandering it was. You know, how it was so cynically put together, all plotted out essentially by toy manufacturers. And especially the way that the title was determined by market research that suggested that “secret” and “wars” were two words that worked well with test groups.

I will say, if you’re giving kids a thrill, you are doing something right. And in terms of the Secret Wars title, Martin Goodman was putting together titles that he thought would be proven sellers constantly, so that canniness was nothing new. There is something to be said for the idea that some things are going to be great for 10-year-old kids but will be terrible for 20-year-olds.

What was it about Marvel that made you focus on it, rather than just write a book about the history of comic books?

Well, I think it goes back to the idea that Marvel is this narrative tapestry that all of these people have worked on and passed on. It’s sort of like television soap operas, but there’s something about that creative ownership that somebody has that’s not lasting, and the proprietary feeling that they have when something that they are a collaborator on doesn’t belong to them at all. It’s due to the way that Marvel ’s storytelling worked — Marvel Comics was this river that rushed by all these people, and they would throw their ideas into this river, and the river would just keep going on without them, it was bigger than any of them. And I think that Marvel is just an extreme example of that kind of thing which exists in the comic book industry.