You attribute the success of Marvel Comics in the ’60s to angst; that their books weren’t just virtuous heroes or ironic horror fables or romance stories. In a comic book Garden of Eden, they introduced angst, the forbidden fruit. How intentional was this conceit?

Very intentional. I mean, it definitely is a big part of the Lee/Ditko/Kirby stuff. I wouldn’t want to try to pin down, any more in than I did in the book, who deserves more credit than that! But yeah, I guess that there was Superman, the ’50s version by Mort Weisinger, was a different kind of angst. But those were all weird surreal explorations of Superman’s id that were pretty weirdly emotional in their own way. But I feel like somebody said, I can’t remember where I heard this, but they said “Marvel Comics characters were all worse off when they became superheroes, their lives were ruined when they got their powers.” Which is kind of true!

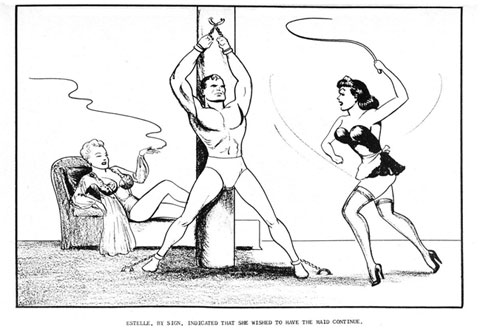

Right: golden age DC characters had under-the-surface hang-ups and perversions, or revealed the perversions of their creators. Like William Moulton Marston and Wonder Woman, his obsession with tying people up and showing Wonder Woman bound and his truth tests mirroring his own psychological work. And of course Superman co-creator Joe Shuster and his S&M/fetish comics work. Whereas Marvel, if you read too much into it, which people our age do, show a world with characters who talk about what they’re thinking and what’s wrong with them, rather than hiding everything behind an alter ego.

It wasn’t like the DC Comics characters never worried about things, but there was something that was so essential about the Marvel characters that they were worrying. Flash worried about stuff in the same way that Green Lantern worried about stuff.

Right, whereas the way, for example, Chris Claremont wrote X-Men, each character had their own way of dealing with their own supernatural reality, which made it seem more real, I suppose, to the reader.

They were definitely self-aware, yeah.

Your book details how Marvel tried to keep up with the times — with African-American characters, female heroes, in the ’60s and ’70s and beyond. Do you think this was a cynical attempt to cash in on things that were happening, or was this an earnest effort to reach out to people and make a grander statement?

I’d say it’s a mix. I don’t think that Black Panther, for instance, was a cynical cash-in. I think Luke Cage may have been a little more cynical! I mean, certainly there’s that moment where they’re launching all these things and there’s this marketing mandate that is like, “We need to reach these different kinds of readers.” For the most part, though, I don’t think social advocacy was at the root of it. I think it was “Let’s tap into these markets.”

Yeah — one can’t help but think of it that way when you read about, say, DC’s new Green Lantern coming out as gay, or X-Men having the first Marvel Comics gay wedding between Northstar and his boyfriend.

What a dumb reason to want to buy a comic book! I mean, I suppose that there could be someone for whom this is their first exposure of someone coming out, that they have to pay four dollars to buy a comic to read about it. But to me, it seems like a weird gimmick.