GATZ Elevator Repair Service pulls The Great Gatsby’s focus back from Jazz Age opulence to themes of fanatical yearning and the callousness of privilege. |

The setting is more boring '90s than Roaring '20s. Gatz, a cult cause célèbre being presented here by the American Repertory Theater (at the Loeb Drama Center through February 7), spins The Great Gatsby, word for word in its entirety, across the grimy surfaces of a contemporary, utilitarian office where what gets done seems as amorphous and insubstantial as West Egg high-roller Jay Gatsby's true identity.

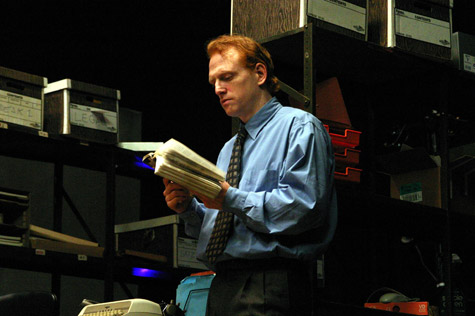

At the beginning of New York–based Elevator Repair Service's six-and-a-half-hour theater piece, which is performed in two parts, a mid-level employee enters with dossier and coffee, tries unsuccessfully to resuscitate his aged computer, and discovers a dog-eared copy of F. Scott Fitzgerald's iconic 1925 novel stuffed into his Rolodex. He starts to read aloud from the found text, tentatively at first, as the low-rent workplace's somewhat Sisyphean business continues its desultory course. Suddenly, a female co-worker is reading over our Nick Carraway stand-in's shoulder, lip-synching the gruff dialogue of Tom Buchanan. And gradually the sparkling, aching business of the novel intrudes on, and then takes over, the mundane business of the office in a spellbinding narrative marathon that is about both the power of prose and the quixotic, ephemeral, even alienating nature of performance.

The late Andy Kaufman used to come on stage at comedy clubs and read from Gatsby until the audience rebelled. So it's probably no coincidence that tucked in amid 19-year-old ERS's œuvre is a piece about the life of Andy Kaufman directed by company founder John Collins, who also does the honors here. But Gatz is no audience-leg-pulling stunt. The power of the novel is exerted at the same time that we see unglamorous nowhere people captivated by art yet ultimately unable to escape — any more than Gatsby can — the dreary confines of their originative milieu. We may not get jazz orchestras playing on the sloping lawns of lit-up Long Island mansions or languid lovelies in floating white dresses. But we do get, read aloud, every rueful, gorgeous phrase Fitzgerald wrote, as well as a deliberately lackluster mirror of some of his themes. And in the tenacious commitment of Scott Shepherd's Nick to the text, even amid the raucous chaos of a Manhattan-afternoon debauch (here enacted amid flung folders and liquor bottles unearthed from metal file cabinets), there is a hint of Fitzgerald's somehow getting the artistic job done at the center of his own personal storm of spendthrift decadence, alcoholic excess, and "careless people."

Some may complain that Gatz is needlessly drab. With its rickety towers of defunct paperwork and windowed plywood corner cage, the office designed by Louisa Thompson is closer to bookie joint than Boston Legal. But the show's marriage of disparate worlds is artful, with sound designer Ben Williams seated on stage providing effects that range from jazz horns and pounded piano to screeching car crashes and chirping crickets (when he isn't playing small parts).