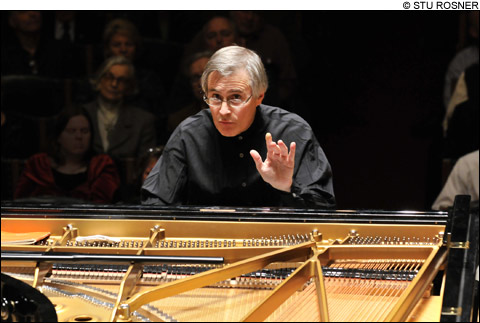

BSO I: Christian Zacharias was articulate and droll in Haydn and Mozart. |

I think the concert I'll remember most vividly from the past few weeks was the closing night of Boston Conservatory's weekend-long tribute to modern-music icon Pierre Boulez on his 85th birthday. For all that Boulez's music is both technically and intellectually challenging, it can also be ravishing — yet few of his pieces get played here. This program began with Boston Conservatory students, under the skillful direction of Eric Hewitt, chair of the Woodwind Department, playing Dérive (1984), six insinuating minutes for six instruments (the quintet called for in Schoenberg's Pierrot lunaire plus percussion), "derived" from the complex chords Boulez had invented for an ambitious piece for orchestra and electronics, Répons (which he himself led at a reconfigured Symphony Hall back in 1986).

Since Dérive, Boulez has been working on an ever-expanding version for 11 instruments that he calls Dérive 2, and that he completed (more or less) in 2006. In Berlin this past September, I heard Daniel Barenboim lead players from his Berlin Staatskapelle Orchestra in both Dérives — the final concert of a two-week (!) tribute to Boulez that included Boulez himself conducting the Berlin Philharmonic. My only previous encounter with Dérive 2 was a 25-minute recording from 2002. At the concert in Berlin, 25 minutes went by, but the ending was nowhere in sight. I wasn't timing it, but it seemed the new version ended up close to an hour long. I loved the music, but I was completely lost.

At Boston Conservatory, in the piece's actual (though "unofficial") US premiere, Hewitt gave us a brief but helpful rundown of its structure: four continuous sections of about 10 minutes each (which Hewitt called "shadow bop," "shadow scherzo," "andante night music," and a "convulsive" mixture of fast and slow) and then, in conclusion, a manic section half that length that Hewitt called "Boulez's answer" to Stravinsky's violent "Danse sacrale" from Lesacre du printemps — the five sections "separated" by what Hewitt referred to as "windows" of calmer, largely unison playing. This piece is not for students — or cowards. Hewitt led a stellar professional ensemble that included violinist Gabriela Diaz and clarinettist Michael Norsworthy, both of whom have performed with Boulez, the BSO's amazing English-horn player Robert Sheena and percussionist Daniel Bauch, and Triple Helix cellist Rhonda Rider. Dérive 2 is a whirlwind of repeated notes in multiple simultaneous syncopated tempos, flashing arpeggios, and pointillist shimmering, perpetual motion with moments of sublime repose and sudden stops — 48 mesmerizing and electrifying minutes. Seully Hall was packed, mainly with students. At the end, a stunned silence was followed by an extended standing ovation.

Another 85th-birthday celebrant, and closer to home, is Gunther Schuller. I'm sorry I didn't get to the New England Conservatory tribute, but Schuller's nearly forgotten though sparklingly jazzy 1958 Woodwind Quintet was the surprise hit of a concert by the Mimesis Ensemble, whose eloquent clarinettist, Vasko Dukovski, also played in a haunting Mahmoud Darwish setting by Mohammed Fairouz. I've heard Yehudi Wyner's demanding Oboe Quartet done with more nuance and drive; on the other hand, I was captivated by four excerpts from Anthony De Ritis's 1999 score for the 1928 psycho-feminist play Machinal.