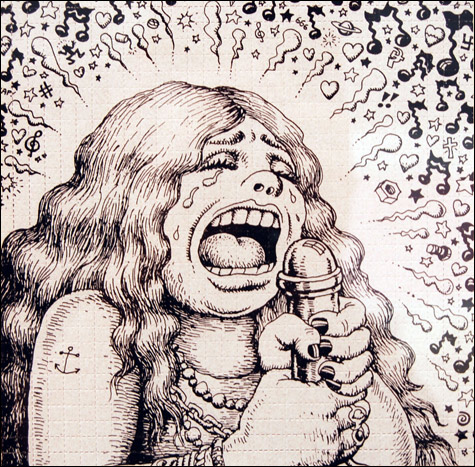

UNTITLED (JANIS JOPLIN) (circa early ’70s) What other artist besides George Grosz so vividly, viscerally channeled the past century? |

“R. Crumb’s Underground” | Paine Gallery, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 621 Huntington Ave, Boston | Through March 7 | Free opening night, February 4, from 6-8 pm

View R. Crumb's Underground slideshow |

Robert Crumb is one of the greatest artists ever. It's as simple as that.Even if the art world doesn't know what to make of his crazy comics filled with drug-induced hallucinations, sadistic sex, racial stereotypes, and cute, carelessly violent cartoon critters that are always on the prowl.

For proof, check out "R. Crumb's Underground," which, put together by the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, opened Monday at Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

The curator is Todd Hignite, a comics scholar and the founding editor of Comic Art magazine. "From the late '60s through the '80s," he astutely notes in the exhibit wall text, "the art world engineered a wholesale extraction of direct human content, mining generations of abstraction, conceptualism, and theory until blood no longer ran from those stones. In the midst of this end game, Crumb rose as a beacon for the missing human passions: individuality, rebellion, and life."

Craving for that missing feeling has led curators to import into the art world graffiti, street art, vernacular photography, commercial graphics, comics, outsider art, and Crumb. Crumb is nothing if not feeling — angry, lusty, lonely, hurt, paranoid, self-loathing, rabid. He's all id all the time. And, oh, is he a mess.

Just how much of a mess became evident in Terry Zwigoff's excellent 1994 documentary film Crumb. It showed the scrawny, geeky social-retard cartoonist in all his super-freakiness and then revealed him as, yes, the most well-adjusted member of his totally screwed-up family. Goodness gracious.

Crumb's genius was to mate awesome drawing chops with the sex, drugs, and revolutionary spirit of the anti-establishment, anti-conformist, anti-consumerist '60s counterculture. His talent arrives fully formed in his earliest comic here, a 10-page Fritz the Cat story from 1965, when Crumb was 22. The randy title character picks up three girls on the street by convincing them that he's a truly sensitive fellow, then gets them into a tub with him naked. The orgy is interrupted when friends barge in (the crowd seems like a nod to the stateroom scene in the Marx Brothers' 1935 film A Night at the Opera) and smoke pot. Then cops break down the door.

In Crumb's world, everything appears tantalizingly available, all options are on the table, all bets are off. Then the Man arrives to put the kibosh on everyone's fun. Or maybe it's just social awkwardness and, as he gets older, aging that squelches the good times.

Crumb draws like a dream. He's not terrific with color — see his mushy 1994 New Yorker cover in which he turns Eustace Tilley into a gangly geek eyeing a flier for "Adult XXX Video." But his mastery of pen and ink is astonishing. Note the 3-D quality of his renderings. It's like reality, but condensed somehow. His work channels the history of cartooning — animated cartoons, newspaper gag strips, adventure and superhero comics, advertising mascots. Feel his joy in the play of his lines. A handful of collaborative jam comics included here reveal that his underground comics peers explored similar subject matter, but none of those peers could match his artistry.

There's still lots that's uncomfortable, if not outright offensive. Like his sweaty, leering voyeurism. Angelfood McSpade is his caricature of an idiot, sex-starved black Amazon, naked except for her leopard-print skirt. "Just a simple primitive creature," he pens on a '68 strip. Even her name is an insult. Or check out his 1970 Jumping Jack Flash comic. It begins with a Charles Manson–type hippie guru mesmerizing a young woman until she eats his shit (not a figure of speech) and then joins his lady cult. The guy gets off on the gals stabbing one another to death; then he fucks the corpses.

In part, he's tweaking holier-than-thou liberal posturing, much as Jules Feiffer did in his Village Voice strips of the '50s and '60s. But Feiffer is always exquisitely refined. Crumb happily wallows in the gutter. There's great fun there.

Yet Crumb — except for when he's rhapsodizing about lust — is forever a contrarian, a curmudgeon. All his characters are either starry-eyed dimwits (usually the voluptuous girls) or jerks (the guys). He seems to have been born a cantankerous old coot. Then he ventures beyond satire into the real, awful thing — misogyny, bigotry, sadism. There's something Nixonian in his sordid grandeur, his Silent Majority reactionary raving against everyone else as phony, stuck-up, spoiled swells, his success mixed with paranoia and loathing — especially loathing of himself.